Making the Xapiri dance: Photography and shamanism in the exhibition Claudia Andujar, The Yanomami Struggle

The xapiri are the images of the yarori ancestors who turned into animals in the beginning of time. This is their real name. You call them ‘spirits’, [sic] but they are other. They came into existence when the forest was still young. The shaman elders have always made them dance and we continue to do like them to this day.[1]

Fig. 1: Claudia Andujar, Woman drinking a calabash of plantain compote, Catrimani, Roraima, 1974. ©Claudia Andujar. Courtesy of Fondation Cartier pour l’art contemporain and Instituto Moreira Salles.

Fig. 2: Claudia Andujar, Gourds full of plantain soup and rasa si peach palm, topped with manioc or taro juice are offered to visitors, Catrimani, Roraima, 1974. ©Claudia Andujar.

The exhibition Claudia Andujar, The Yanomami Struggle, held at Fondation Cartier pour l’art contemporain (Cartier Foundation for Contemporary Art, https://www.fondationcartier.com/en/exhibitions/claudia-andujar-lalutteyanomami) from 30 January to 10 May 2020 is the most extensive retrospective to date dedicated to the work of the photographer and activist Claudia Andujar. For over five decades Andujar (born in Neuchâtel, raised in Transylvania, and based in Brazil since 1955) has devoted her life to photographing and struggling for the rights of the Yanomami, a group of approximately 36,000 Amerindian people living in an area of around 180,000 km2 in the Amazon rainforest along the Brazilian-Venezuelan border. Curated by Thyago Nogueira and assisted by Valentina Tong, for the Instituto Moreira Salles in Brazil, and based on four years of research in Andujar’s archive, with the active collaboration of the photographer, the exhibition brings together around 300 photographs, a series of Yanomami drawings, films, books, and other documents, most of which are shown for the first time, as well as the audiovisual installation Genocide of the Yanomami: Death of Brazil (1989-2018). This last piece was specially re-designed for the exhibition, which was held previously at Instituto Moreira Salles in São Paulo and Rio de Janeiro. As part of a joint partnership between Foundation Cartier pour l’art contemporain and Triennale Milano, the exhibition is scheduled to be shown in Milan in Autumn 2020.

On many occasions Fondation Cartier pour l’art contemporain has shown interest in figures who, through their aesthetic or scientific production, approach issues related to ecology, cosmopolitics, as well as the culture and rights of the Amerindian peoples. This was the case in the Foundation’s previous exhibition, Nous les Arbres (Trees), curated by the anthropologist Bruce Albert (who has worked among the Yanomami for over four decades and was a scientific advisor for the current show), Hervé Chandès, and Isabelle Gaudefroy. Nous les Arbres showed works by Andujar, the Paraguayan filmmaker Paz Encina, and Yanomami artists such as Joseca and Kalepi, among other contributors. The increasing focus of French and international museological institutions on politico-ecological questions is a powerful indicator of the state of the world. Nevertheless, it is also relevant to question the political and epistemological consequences of exhibition initiatives entailing the risk of ‘aesthetic deterritorialisation’[2] and depoliticisation of those questions and to problematise the function – and the status – of the so-called ‘indigenous art’ in the politics of contemporary art and, in particular, the politics of Fondation Cartier, an institution created in 1984 by the luxury brand Cartier.[3]

The structure of the exhibition, divided into two main sections, reflects the remarkable contribution of Andujar both to the history and the aesthetics of photography, and the defence of the Yanomami people. The first section, displayed on the ground floor, is devoted to Andujar’s ‘artistic’ work, which is represented in the collections of the Foundation. Assembling photographs of Andujar’s first seven years living with the Yanomami, the opening section restitutes the evolution of the photographer’s gaze on their world and culture – in short, the transition from the observation of rituality to the ritualisation of the photographic process itself, as it will be developed further. This section raises the question of how the adoption of a system of co-representation based on Yanomami communitarianism shaped the aesthetics of Andujar’s photographic work.

The second section, held in the basement, shows Andujar’s work as an activist when, besides photographically interpreting Yanomami culture, she used photography as an instrument for political change. Additionally, this section features Andujar’s book Amazônia (1978), edited in collaboration with George Leary Love, the large-scale installation Genocide of the Yanomami: Death of Brazil, and Yanomami drawings, along with several other pieces and documents. Each page of Amazônia, a book with no text and a strong cinematic dimension, is displayed separately in a long rectangular table. The scenographic arrangement creates a double movement as the visitor is invited to follow the progression of the visual récit physically. Synchrony and asynchrony structure Genocide of the Yanomami: Death of Brazil, a montage of a vast photographic corpus screened with multiple channel projections on multiple screen constructions surrounding the viewer. This viewing dispositif breaks the tradition of cinematic perspective, constructing an experience of non-linear and coexisting times, in line with the Yanomami cosmology and cosmovision traversing Andujar’s photographic work as a whole.

The scenography is, indeed, an important element of the overall concept of the exhibition. The multi-layered and arborescent scenographic structures, resembling the branching pattern of trees and their subterranean stem, seem to evoke the ‘mobile and polyvalent architecture of the Yanomami territoriality’,[4] the ‘rhizomatic geometry’ of the cosmopolitical urihi concept, the ‘forest land’, which is conceived as a ‘living entity, part of a complex cosmology including humans and non-humans’.[5] The semi-transparent architectonic structure of the Foundation, designed by Jean Nouvel and inaugurated in 1994, making the green surrounds reflect on the works displayed on the ground floor, reinforces this aspect as it blurs the borders between inside and outside, merging the internal and external elements into an organic continuity. The scenographic structures feature excellent colour and black-and-white photographic prints of the Yanomami daily life, rites, walks in the forest, and architectures, as the collective houses named yano or xapono. These elements, along with films such as Marcello Tassara’s Povo da Lua, Povo do Sangue (1984), resulting from the assembly of part of Andujar’s photographic archives, offers the spectator a consistent panoramic view of the photographer’s work and a deep insight into the history, culture, cosmology, and cosmovision of this semi-nomadic hunter-gatherer group. The exhibition is accompanied by a 336-page beautifully-designed catalogue containing texts by Andujar, Albert, and Nogueira, photographs, and a broad set of related documents.

Andujar’s work enters into dialogue with different disciplinary fields and aesthetic traditions against the background of the artist’s cosmopolitan biography. The tragic experience of the Shoah marks the early years of the photographer, who at the age of fifteen moved to New York, where she studied at Hunter College. Yanomami communitarianism re-signifies, for the artist, her diasporic trajectory. In her words,

This world [the Yanomami world] helps me understand myself and accept the other world in which I grew up. These two worlds come together… To me, they are one world.[6]

This statement suggests an auto-ethnographic shift of the gaze[7] (i.e., observing herself and Western culture through the observation of the Yanomami and from the Yanomami perspective) and a powerful inter-epistemic alliance between the two worlds. It also points, as will be tackled later, to the overturn of the opposition between aesthetic inventiveness (through specific experimental formal procedures) and an ethnographic dimension (the observation and representation of otherness and the questioning of this process), which is especially relevant in Andujar’s early work with the Yanomami. This opposition is, indeed, particularly present in the featured photographs of the first month spent by Andujar with the Yanomami in 1972 while on a Guggenheim Fellowship[8], remarkable images with a strong ethnographic dimension even if detached from colonial representations of landscape, nature, and the human figure. As the work of the photographer moves away from the dominant Western representative and epistemic paradigms, overcoming the aesthetic-anthropological opposition, which for James Clifford is ‘systematic’[9] in the twentieth century, particularly in the agenda of the early avant-gardes, the associated categories and dual structures are rearranged, a process that gives origin to expanded integrated inter-relations between disciplines and practices, and a representative and semiotic ecology. The photographer’s subsequent work, developed within a system of horizontality and co-representation – both in representative and epistemic terms and concerning its modes of production – based on Yanomami communitarianism, is marked, in fact, by the alliance between heterogeneous visual regimes and epistemological paradigms.

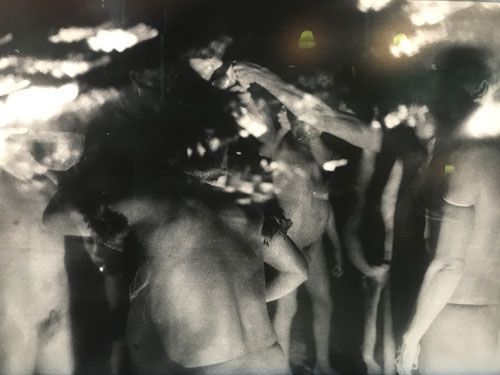

The process of ‘becoming-other’ is fundamental for the Yanomami culture and its shamanic practices.[10] Living with the Yanomami for long periods throughout the 1970s, a decade covered by the first section of the exhibition, Andujar explores the process of becoming-other that is constitutive of their culture, establishing articulations between the material and the ritual spheres, the human and the non-human fields, the visible, and the invisible realms. Her photographs affirm an inter-visuality and an inter-epistemology, a cosmopolitical dialogue between the ‘modern Western world’, where she comes from, and the Yanomami culture and cosmovision. Andujar’s work may be, therefore, regarded as one of the most fulgent encounters between photography (as Andrea Tonacci and Juan Downey, among others, for cinema/video), as a techno-ideological apparatus and a representational practice inscribed in the scopic regimes of Western modernity and historically related to colonialism and coloniality (and the associated categories), with Amerindian visual and epistemic traditions. This process has consequences at the epistemic and representative levels, such as the redefinition of the conventional binary relationship between the subject and the object of knowledge and representation, which is overturned through the agencement, proliferation, and circulation of perceptive and cognitive perspectives. Also, shamanic thought is fundamental in the constitution of inter-visuality and inter-epistemology in the work of Andujar. The Yanomami shamanic practices lead to the world of the Xapiri spirits and, according to Davi Kopenawa and Albert, to ‘true’ knowledge of the images of the world.[11] Through different photographic procedures linked to shamanic rituality, Andujar’s work makes visible the invisible (for the non-shamanic human beings) world of the xapiri spectres, affirming, therefore, a continuity – and contiguity – between the visible and the invisible realms structuring Yanomami cosmology and cosmovision. As the Yanomami shamans in the ‘ontological diplomacy’[12] of the yãkoana (hallucinogenic powder), plantain soup and rasa si peach palm fruit juice ritual ceremonies, Andujar’s photographs make the xapiri spirits dance in the photographic surface (Figs 1, 2).

Since their invention, photography and cinema articulate the representation of ritual with processes of ritualisation. Approaching photography and cinema from the perspective of ritual implies thinking photographic and cinematic images as points of fixation of ‘reality’ that not only aim to reproduce it, but also to transform it and go beyond it, making visible the invisible. From the spirit photographic experiences of the late nineteenth century to the emphasis of the early twentieth century avant-garde’s theories on the moving image’s capacity to restore the experience of the ritual and the sacred that was suppressed by modern rationality, photography and cinema, despite their claimed mechanical objectivity and automatism, enabled other ways of seeing and perceiving. Photography and cinema affirmed their capacity to re-enchant the world and transfigure ‘reality’ – and to represent altered experiences and states of consciousness – in connection to ritual and myth. Andujar’s work may be related to this genealogy of early practices and conceptions of photography and cinema. If Clifford[13] and David MacDougall[14] highlight the connection between the agenda of the early avant-gardes and that of early anthropologists, Andujar’s photographs displace the ideological and dynamic borders between aesthetics and ethnography, overturning their opposition – and even claiming their redefinition – through cosmopolitics, inter-visuality, inter-epistemology, and experimental processes of co-representation. Through procedures such as the application of vaseline on the lenses, or the usage of infra-reds and slow shutter speed, Andujar renders photographically visible the shamanic chants, words, and invocations, and the invisible luminous world of the xapiri. Profaning the apparatus through unconventional usages and unprogrammed results,[15] the photographer represents shamanic rituality through the ritualisation of the photographic process itself.

The observation, participation, and interaction in shamanic rituals determine the adoption of formal experimental procedures going further beyond conventional ethnographic representative techniques and epistemic presuppositions. Making visible the invisible world of the xapiri and tending to the ritualisation of image-making, these contextual procedures, developed in situ and as a reaction to – or part of – the Yanonami shamanic rituality and performativity, also suggest the need for a phenomenological and an ontological review of photography. Furthermore, as it combines experimental aesthetic procedures with the horizontal re-structuring of the conventional epistemic and representative positions of the observer and the observed in ethnography and visual anthropology as scientific disciplines,[16] Andujar’s work short-circuits the historical borders between the formal and observational modalities, pointing to the possibility of non-exclusion and dynamic integration of the domains of art and ethnography.

The photograph Woman drinking a calabash of plantain compote taken in Catrimani (Roraima) in 1974 and displayed in the second room of the first section of the exhibition (Fig. 1), exemplify the articulation between the representation of shamanic rituality and the ritualisation of the photographic process within a system of co-representation based upon Yanomami communitarianism. The reahu, a great intercommunal feast, is, according to Albert,[17] both a ceremony of political alliance and a funeral rite. Kopenawa describes the Yanomami shamanic ritual practised on these occasions: ‘If we drink a lot of plantain soup or peach palm fruit juice at a feast, we become other.’[18] The photograph represents shamanic rituality, entranced bodies wearing ornaments considered as clumsy imitations of those worn by the spirits, rendering visible the continuity, according to the Yanomami cosmology, between the visible world and the invisible realm of the xapiri. Those are presented in the photographic surface as luminous spectres, halos of light, through the usage of experimental photographic procedures aiming to express shamanic rituality, and pointing to the performative interaction of the photographer with the collective states of trance and possession. If intentional photography is always an emotional-cognitive reaction to a given empirical situation, Andujar’s photographs might be not only regarded as the result of a shamanic ritual, but also as an example of shamanic photography. Additionally, the images immerse the viewer in a shamanic space-time.

Photography becomes an indexical manifestation – despite the theoretically phenomenological impossibility – of shamanic thought and rituality. Andujar’s work explores the transitions between the visible and the invisible that structure Yanomami culture and its shamanic practices, claiming for a phenomenological and an ontological review of photography. The hypothesis of a ‘transformative mimêsis’ or, in other words, an anti-ontological – or an ontologically expanded – conception of photography, conceived now in terms of separation and not uniquely of reproduction of empirical ‘reality’, underlies Andujar’s operating procedures. To apprehend the photographer’s work according to a Yanomami perspective would, therefore, entail reflecting on the way the photographic medium conjugates the relationship between the visible and the invisible, and how it breaks the barrier between thought, emotion, and trance. In Andujar’s work, photographic procedures open passageways between the Yanomami visible world and the invisible realm of the xapiri, affirming a continuity – and contiguity – between the two spheres in line with the local cosmology and cosmovision, which find correspondence in the photographic practice – and in the conception of photography – itself.

The second room of the exhibition’s first section emphasises then the ritualisation of the photographic practice as a significant aspect of Andujar’s work. In the catalogue Nogueira refers to an experience Andujar made with the yãkoana powder,[19] pointing to the photographer’s empirical knowledge of the Yanomami shamanic rituality, to her becoming-Yanomami – and, in parallel, to the auto-ethnographic process described above. In the reahu photographic series, photography becomes a ritual itself in a dynamic choreography of bodies and images. Affirming the corporeal and sensorial dimensions of image-making, in the framework of a system of exchange, affection, and empathy, this series inscribes in a regime of co-representation based on Yanomami communitarianism. There is an attempt to redefine, through co-representation, the conventional binary relationship of the observer and the observed in horizontal dynamic terms. The photographic forms embody the tensions between the observer and the observed in the intense synchrony of the present. If photography conveys Andujar’s perspective on the Yanomami rituality, the different ways of capturing the reahu (slow shutter speed, usage of flashes and oil lamps producing luminosity effects) seek to present the individual and collective sensory experience of the ritual and to render photographically visible the invisible. Transfigurative technical procedures such as the multiple exposure of a single frame, as in the photograph Gourds full of plantain soup and rasa si peach palm, topped with manioc or taro juice are offered to visitors (Catrimani, 1974, Fig. 2), aim, additionally, to give formal expression to Andujar’s point of view and the Yanomami perspective concurrently. The superposition of different scenes in the same frame not only suggests the cognitive connection between the observer and the observed (eventually involving the viewer) but also affirms a non-linear, non-sequential, and cyclical conception of time in line with the Yanomami cosmology and cosmovision. The parallax perspective, i.e. the representation of a scene as seen simultaneously from different positions, puts forward the circulation of multiple perspectives, entwined inter-specific, and inter-semiotic relationships.

As it represents ritual through the ritualisation of image-making, Andujar’s work allows reconsidering certain dualistic structures of the hegemonic European modernity, particularly the relationship between the observer and the observed, the subject and the object of representation and knowledge, and the opposition between subjectivity and objectivity. In parallel, it points to the dissolution of the separation between the material and the ritual spheres through an intensive sensory regard. Those are redefined through inter-visuality and inter-epistemology, along with a representative and semiotic ecology founded upon the circulation of human and non-human perspectives (machinic, animal, vegetal, mineral, and spectral, as, according to the Yanomami cosmology, the shamans not only see the xapiri but are also seen by them), in line with certain anthropological conceptions such as Eduardo Viveiros de Castro’s Amerindian Perspectivism.[20] In some cases, as exemplified above, the communication between multiple points of view acquires photographic visibility through the multiple exposure of a single photogram, a procedure overlaying and multiplying the visual elements, rendering visible the spectrality of the shamanic rituals, and suggesting possible alternative scopic paradigms.

The structure of the exhibition points to co-representation, but also to self-representation processes. In addition to the Yanomami drawings, part of a project developed from 1974-1977 with the collaboration of the missionary Carlo Zacquini, a permanent ally of the photographer, it also features the first Yanomami film, Morzaniel Iramari Yanomami’s Urihi Haromatimape: Curadores da terra-floresta (Healers of the Forest Land, 2013). Documenting a reahu, Urihi Haromatimap affirms, according to André Brasil, ‘images-spirit’, allowing ‘to see through [sic] the invisible’.[21] The singular articulation between the visible and the invisible Brasil highlights may be related to Andujar’s shamanic photography. Photography, as a visual medium par excellence, becomes an instrument for the inscription of both the visible and the invisible realms. Moreover, in the same way as shamans have, according to the Yanomami cosmology, the ability to invoke the invisible world to transform the visible world (the healing process), Andujar’s work also suggests the hypothesis that the visible realm can be transformed from the invisible realm through the photographic process and her singular approach to photography. Focused on the photographer’s work as an activist, the second part of the exhibition seems to confirm this possibility. In 1978 she founded the Commission for the Creation of a Yanomami Park with Albert and Zacquini. From that year on, photography was assumed as a political performative tool. In 1991, after the end of the military dictatorship in Brasil (1964-1985), the Yanomami Park was officially demarcated and approved and registered the following year. Andujar’s photographs were a fundamental instrument in this process as they divulged the Yanomami struggle both in Brazil and internationally.

The Yanomami Struggle is a fundamental exhibition not only due to the aesthetico-political and epistemic qualities of the work it features, but also because it puts Andujar’s intermedial archive in circulation in our complex particular historico-political conjuncture. In a period of accelerated integration of the natural sphere into the global capitalist system and imminent ecological catastrophe, Yanomami survival is being threatened again by the genocidal developmental policies of Jaír Bolsonaro’s government, an aspect that is strongly highlighted and denounced in the exhibition. If, for the Yanomami, the ‘forest land’ is not an external domain to society but, in the words of Albert, ‘a large living entity’,[22] Andujar’s work demonstrates how the cosmological, political, and epistemological thought and knowledge of the Amerindian peoples are models of relativist tolerance, and sustained and harmonious forms of life. Years ago, immersed in the immensity of the Ecuadorian Amazonian rainforest, I remember feeling for the first time the forest as a living entity giving me acute consciousness of the urgency of learning from the Amerindian peoples. Andujar’s work echoes that call, underscoring the importance of eco- and cosmopolitics.

Raquel Schefer (Sorbonne Nouvelle – Paris 3 / University of Lisbon / University of the Western Cape)

References

Agamben, G. Qu’est-ce qu’un dispositif ? Paris: Rivages Poche / Petite Bibliothèque, 2007.

Albert, B. Temps du sang, temps des cendres: Représentation de la maladie, espace politique et système rituel chez les Yanomami du sud-est (Amazonie brésilienne). Ph.D. diss., Université de Paris X Nanterre, 1985.

Albert, B. ‘Un monde dont le nom est la forêt, hommage à Napëyoma’ in Claudia Andujar: The Yanomami Struggle (exhibition catalogue). Paris: Fondation Cartier pour l’art contemporain, 2019: 102-110.

Brasil, A. ‘Ver por meio do invisível. O cinema como tradução xamânica’ in Ameríndias: Performances do cinema indígena no Brasil. Lisbon: Sistema Solar, 2019: 95-119.

Clifford, J. The predicament of culture: Twentieth-century ethnography, literature, and art. Cambridge-London, Harvard University Press, 1988.

Flusser, V. Ensaio sobre a Fotografia. Para uma Filosofia da Técnica. Lisbon: Relógio d ́Água, 1998.

Jameson, F. ‘Transformations of the image in Postmodernity’ in The cultural turn: Selected writings in the postmodernity. London-New York: Verso, 1998.

Kopenawa, D. and Albert, B. The falling sky: Words of a Yanomami shaman. Cambridge-London: Harvard University Press, 2013.

MacDougall, D. Film, ethnography, and the senses: The corporeal image. Princeton-Oxford: Princeton University Press, 2006.

Nogueira, T. ‘Claudia Andujar. La Lutte Yanomami’ in Claudia Andujar: The Yanomami Struggle (exhibition catalogue). Paris: Fondation Cartier pour l’art contemporain, 2019: 161-269.

Vancheri, L. Cinémas contemporains. Du film à l’installation. Lyon: 2009.

Viveiros de Castro, E. A Inconstância da Alma Selvagem e Outros Ensaios de Antropologia. São Paulo: Cosac Naify, 2002.

[1] Kopenawa & Albert 2013, p. 74.

2 Reinterpretation of Luc Vancheri’s notion of ‘aesthetic deterritorialisation’ (Vancheri 2008).

[3] It is important to remark that gold exploration is a significant cause of environmental (and political) issues such as deforestation and soil degradation, particularly in developing countries like South Africa, a nation with a complex mining labour history linked to the history of colonialism and apartheid. In this frame, Fondation Cartier’s interest in ecology and cosmopolitics seems to be a key strategy for publicly affirming Cartier’s ecological engagement. At the same time, it might be relevant to mention that issues related to ecology and cosmopolitics come together in French and international museological institutions with questions linked to the history of political struggle and liberation movements in the twentieth century, as, for instance, in the exhibitions After Year Zero: Geographies of Collaboration since 1945 (Haus der Kulturen der Welt and Warsaw Modern Art Museum, 2013-15, commissioned by Annett Busch and Anselm Frank) and Uprisings (Jeu de Paume Museum and other museological institutions worldwide, 2016-17, curated by Georges Didi-Huberman). The weight of these subjects in the art agenda might derive from the ‘exoticisation’ (and aestheticisation) of political history, ‘extra-modern’ cultures and non-Western epistemologies, a fascination with what is temporally or spatially (or both) distant from the enunciative context. This process often entails the omission of issues related to contemporary political movements – and their insurrectional potentiality – in the Global North.

[4] Albert 2019, p. 110, my translation. All translations are my own.

[5] Ibid., p. 106.

[6] Andujar, quoted in Nogueira 2019, p. 193.

[7] An allusion to Fredric Jameson’s notion of ‘gaze’s shift’ (Jameson 1998, p. 107).

[8] Andujar was the recipient of two Guggenheim Fellowships, the first one in 1971-72, and the second in 1977.

[9] Clifford 1998, p. 200.

[10] Kopenawa & Albert 2013.

[11] Ibid.

[12] Albert 2019, p. 107 (my translation).

[13] Clifford 1988.

[14] MacDougall 2006, p. 57.

[15] Evocation of Vilém Flusser and Giorgio Agamben’s conceptions (Flusser 1998; Agamben 2007).

[16] Besides the already mentioned cases of Tonacci and Downey, similar démarches may be found in the field of cinema and video, as for instance in the work of Jorge Prelorán and Trinh T. Minh-Ha.

[17] Albert 1985.

[18] Kopenawa & Albert 2013, p. 148.

[19] Nogueira 2019, p. 196.

[20] Viveiros de Castro 2002.

[21] Brasil 2019, p. 110.

[22] Albert 2019, p. 106.