Acts of laughter, acts of tears: The production of ‘truth-effects’ in Oriana Fox’s ‘The O Show’ and Gillian Wearing’s ‘Self Made’

by Maria Walsh

There was a time in the not too distant past when, in theory at least, claiming the truth of one’s identity was viewed with suspicion. In poststructuralist theories, particularly of the psychoanalytic persuasion, the subject is split from knowing itself and thereby from proffering a unified identity. Truth here is at best provisional, at worst deceptive or even damaging, as its profession disavows the internal opacity of the subject, projecting it outwards in witting or unwitting acts of domination and exclusion of others. However, the notion of truth has transmogrified in the contemporary landscape of neoliberal capitalism and digital technology, two interrelated phenomena which, in their seeming immateriality, seem to have ushered in a new desire for authenticity. But rather than authenticity here having to do with retreating from what Lionel Trilling refers to as the ‘loss of personal integrity and dignity entailed by impersonations of social existence’,[1] this new authenticity incorporates these impersonations, using them to profess ‘truths’ more akin to his description of sincerity as that which is not truth, but in ‘not being false’ is heartfelt.[2]

The performance of public acts of sincerity is key to this new kind of authenticity, which is desirous of personal, if not societal, change. In the global West, the shift from identity politics as a demand for collective rights to becoming a cultural expression of individuals has resulted in cultural production being seen as a site of transformation and hope in lieu of organised politics. Transformation in this context is infused with popularised therapeutic discourses of self-development and recovery which are presented on reality television and online media support forums.[3] However, rather than returning the self to a core authenticity outside of social exchange, the emphasis in contemporary cultural production is on the creation of sincere behaviours contagiously circulated among subjects. My wager in this article is that, as Adam Kelly succinctly puts it, for a post-postmodern generation, an ‘unillusioned acknowledgement of formula’ dialectically sits ‘alongside a barely repressed hope or belief that such formula need not entirely negate the expression of something genuine and real’.[4] While online platforms and other media phenomena such as reality television are ubiquitous sites for the production of sincerity as affects ‘that are circulated among subjects’,[5] so too are artworks.

In what follows, I explore the therapeutic dynamics of sincere performancesin relation to two artists’ moving image works: Oriana Fox’s The O Show (2011-ongoing) and Gillian Wearing’s Self Made (2010). Both works obliquely reference the therapeutic makeover narratives of reality television, both in the confessional chat show and the group survival show modes. Fox’s The O Show can be situated alongside the ubiquity of therapeutic narratives on online platforms in that the initial performance of the show was live streamed on www.stickam.com (no longer online) and excerpts of some of the resulting videos can be found on Vimeo. Wearing’s film by contrast is an artist’s experimental documentary screened at film festivals and released on DVD, but the confessional mode of reality television and the survival narrative of endurance shows also inform its questioning of the ‘truth’ of identity (both works also feature the Method acting coach Sam Rumbelow, but more about him later). In their different ways, both artworks engage with the therapeutic value of generating acts of sincerity that proffer‘truth-effects’ of identity in which there is a slippage between the sincere as performative truth act and authenticity as a genuine truth.

This is not out of keeping with the origins of the discourse of sincerity which, from its beginnings in the 17thcentury, was always a duplicitous entity. It depended on ‘a congruence between avowal and actual feeling’,[6] yet at the same time recognition of this split ‘assaults the traditional integration that marks sincerity’.[7] Performative techniques are required to enable sincerity. Traditionally, rhetoric was one such technique. Then as now, the theatricality of sincerity consists in ‘its bodily, linguistic and social performances and the success or felicitousness of such performances’.[8] In the contemporary sphere, this success or felicitousness is not dependent on a perceived integration of inner and outer, surface and depth, but on the performative nature of social exchange. As in J.L. Austin’s speech-situations, which Ernst van Alphen and Mieke Bal infer in the earlier citation, performative statements are neither true nor false but happy (felicitous) or unhappy (infelicitous). An infelicitous (unhappy) performative might not deliver on an act (for example, of a promise) that it enunciates. In this sense, its speaker could be considered insincere, but nonetheless the utterance produces an effect of truth in the speech-situation in which it is uttered in that it prompts the action of another. In this then, ‘truth-effects’ are social, dependent on others to validate their authenticity regardless of the interior life of the speaker.

In using the term ‘truth-effect’ I am loosely combining Michel Foucault’s notion of a ‘regime of truth’ with Austin’s felicitous or infelicitous performatives. Foucault’s notion of truth is also performative in the sense that it necessitates techniques of production of which a speech act would be one. A regime of truth describes

the types of discourse which [each society] accepts and makes function as true; the mechanisms and instances which enable one to distinguish true and false statements, the means by which each is sanctioned; the techniques and procedures accorded value in the acquisition of truth; the status of those who are charged with saying what counts as true (my emphasis).[9]

I am less concerned with the reification of ‘truth’ in authority figures than with Foucault’s emphasis on techniques and procedures for the production of what counts as true or felicitous.

The mechanisms or techniques used to produce ‘truth-effects’ of identity in my respective case studies are: Rational Emotive Behaviour Therapy (R.E.B.T.), a form of therapy invented by Dr. Albert Ellis in the mid 1950s, and Method, an acting technique developed in the early 20th century by the Russian theatre director and actor Konstantin Stanislavski. R.E.B.T. is explicitly referred to on Episode 4 of Fox’s The O Show (2012), one of her three guests being her real life R.E.B.T. therapist Bernadette Ainsworth. As opposed to Ainsworth’s bio-psychosocial model of emotional disturbance which may be remedied in as little as a couple of sessions, the other two guests – a psychodynamic therapist, Liz Bentley, and Rumbelow – refer to the extended temporality of ‘sitting with an emotion’. We glimpse what this might mean in Wearing’s Self Made, in which Rumbelow, the film’s main protagonist, deploys Method as a technique to enable seven non-actor participants to each make a personal short film within the documentary itself.

There are uncanny parallels between R.E.B.T. and Method as therapeutic techniques of producing ‘truth-effects’ of and for selfhood in contemporary culture. Both of them deploy an imaginatively constructed artifice to engender a kind of authenticity that has more to do with the sincerity of social performances than with the modern self-alienating consciousness of individual introspection, which Trilling discusses in Sincerity and Authenticity as stemming from Hegel, who saw authenticity as being opposed to sincerity. Hegel’s self-alienating consciousness of individual introspection departs from dominant ideology in a bid for freedom which entails sacrifice and renunciation,[10] values which are not conducive to the therapeutic narratives of self-recovery and well-being which dominate in the cultural and educational spheres of contemporary cognitive capitalism. However, in an era in which these therapeutic narratives are seen as remedying the fracturing of traditional concepts of identity that ensue from social, economic, and technological change,[11] the question arises as to whether they simply solder the self to the reduction of identity to cliché and branding that circulates in consumerist capitalism or whether there might be a more socially transformative potential to ‘heartfelt’ performances in which sincerity is acted out.

The O Show

Fig. 1: Oriana Fox, The O Show, promotional image, 2011. Courtesy of the artist.

Fox’s The O Show reprises her interest in televisual media narratives of self-improvement in her video Our Bodies, Ourselves (2003), her remake of the television series Sex and the City, in which she acted the roles of all four female characters, mashing the consumerist romantic narrative of the series with second wave feminist art techniques such as needlework and embroidery (historically, the latter were key to female emancipation and autonomy). Self-improvement through exercise and decisive action also feature in later videos such as The Embodiment Workout (2005) and Excess Baggage (2007). Fox is at the centre of these videos in more than one sense. She not only appears in them, but also explores her own emotional and cognitive interpellation as a woman of her generation in the global West. We see this evidenced most clearly in 3 into 1 (2004), in which Fox plays herself and the roles of her mother and father, both psychologists, all three discussing ‘Ori’s’psychological problems. Fox’s mother, Angela Monti Fox, a psychodynamic psychoanalyst, is brought on as a guest in Episode 2 of The O Show to advise a performance artist friend of Fox’s on her love life. Fox states that The O Show is about the therapeutic potential of performance. Episode 4 (the focus of this article) features Fox interviewing her R.E.B.T.therapist, Bernadette Ainsworth. Ainsworth, who previously worked as an actress, is a persuasive advocate of R.E.B.T.. She charismatically professes how the therapy transforms people for the better, solving personal anxieties and emotional disturbances more successfully than other therapies such as psychoanalysis, which she disparages as being unnecessarily time consuming and expensive.

The premise of R.E.B.T. is emotional responsibility which advocates that one can choose how to think and feel about situations – in other words a crude kind of performativity dependent on a volitional subject in control of its destiny rather than being inhibited by the ‘constitutive constraints’[12] of body and psyche. Ainsworth asserts how, after trying various psychoanalytic and psychodynamic therapies, R.E.B.T. was the therapy that finally worked for Fox. Breezily aligning this ethos with consumerist capitalist society without acknowledging any ideological rationale, she attributes the success of R.E.B.T. to its capacity to achieve ‘fast, efficient and speedy results’, Fox being living proof of this. ‘That is the narrative!’, Fox retorts as if there is some doubt about its being true, though the camera’s deliberate gaze on Fox’s pregnant belly seems to further underscore Ainsworth’s success in enabling Fox’s achievements. Fox is both artist as glamorous faux-television host and a future mother, both roles endorsed as fulfilling the social contract to be re/productive.

Fig. 2: Oriana Fox, The O Show: The Therapeutic Potential of Performance, 2012 (video still). Courtesy of the artist.

Fox sardonically blogs that ‘the techniques illuminated by these professionals can be employed towards achieving ever increasing happiness, self-actualization and creative productivity’.[13] Her art chat show would appear to enact this statement at its word, particularly in relation to the R.E.B.T. technique of shame attacking. This technique advocates an approach to personal problems in which the client, on the road to total self-acceptance, deliberately acts in a way they fear might incite judgment from others.Fox calls this ‘acting against one’s irrational beliefs’; Ainsworth refers to ‘exposure and response prevention’. Surviving the act, a person realises that no one is judging them and that nothing bad happens if they act in this way. In Fox’s case, this entailed the repeated pretence of being confident to enable her to actually becomemore confident and be cured of shyness, a kind of ‘fake it till you make it’ production of identity.[14] This is a ‘truth-effect’ in the sense that the iteration of the speech-act ‘I am confident’ produces truths in the futuristic temporality of becoming rather than adhering to a notion of truth as fixed in the past, e.g. ‘I am shy and nothing will change that.’

Exposure therapy

The ubiquity of this kind of therapeutic narrative can be seen in other artists’ work. Without referring to R.E.B.T., the artist Ann Hirsch describes her YouTube performances as the character Caroline Benton on her vlog Scandalishious (2010) as a form of ‘exposure therapy’.[15] Benton is a twenty-something hipster with a squeaky cloying voice who performs song and dance routines for her followers as well as confessing her anxieties and desires. Hirsch’s discussion of this fits with the therapeutic narrative of self-esteem:

[w]hile I was growing up and becoming a woman, I hated myself. I knew I was smart but other than that I thought I was just a disgusting girl that no one could be sexually interested in. I started performing as Scandalishious because I was tired of feeling that way. Or at least, I was tired of appearing as though I felt that way. So I started pretending I thought I was sexy and I quickly learned that if I pretended to be confident, people would believe it. And then I actually became more confident as a result.[16]

While on the one hand this persona enables her to mimic the narcissism of online female subjectivities, it is also a vehicle to express and work on Hirsch’s own feelings of insecurity and shame around sexuality. Admitting that Caroline both is and is not her, Hirsch could be said to use this character to act against irrational beliefs that in the philosophy of R.E.B.T. would be seen as stemming from subconscious core ideas and attachment to ‘underlying “rules” about how the world and life should be’ rather than how it actually is.[17] While the misogyny that Hirsch purports to have imbibed unconsciously does exist, her decision to act against how that phenomenon has affected her resonates with R.E.B.T. training which advocates moving away from applying general traits to rate the ‘self’, e.g. ‘a bad thing happened to me in the past therefore I am bad and unworthy’.

The emphasis on acting as a way of producing ‘truth-effects’ of the self is very different to the proclaiming of one’s truth in art discourse of the 1990s, which was more concerned with group identity politics as the ground from which political transformation could be demanded. Early in the decade, art historian Hal Foster was critical of confessional art by artists such as Sue Williams and of reality television chat shows for naturalising damaged, victimised, and traumatised bodies as an ur-ground of authentic experience.[18] His reasoning was that this recourse to personal trauma makes experience impossible to challenge or criticise, as the subject becomes the arbiter of his or her truth as irrefutable. If, as Frank Furedi recounts, the idiom of therapeutics to describe the self spiraled in the 1990s, its initial emphasis on trauma as a particular overwhelming form of experience was gradually transformed by the end of the decade to become a figure of speech referring to little more than people’s response to an unpleasant situation.[19]

His polemical view somewhat echoes that of sociologist Eva Illouz writing in 2007 of how therapeutic communication in cognitive capitalism instils a procedural quality to emotional life in which emotions are conceived as objects to be measured. In this development, emotions become divorced from their fluctuating situational contexts and more compatible with ‘a language of rights and of economic productivity’.[20]According to Illouz (who I agree with) negative emotions such as guilt, anger, resentment, shame, or frustration are neutralised in the subjection of emotional relationships to institutional management procedures. In the contemporary workplace, the use of therapeutic narratives of self-realisation and autonomy emphasises self-confidence, low self-esteem being considered like a trauma which needs overcoming. Cognitive behavioural therapies, of which R.E.B.T. is one, are useful in this context in that they produce immediate and measurable results. While the R.E.B.T. technique of shame-attacking, in enabling people to overcome their fears by acting them out, seems laudable, it also succumbs to an underlying belief that in our cognitive capitalist era we have both the right to and the responsibility for our own well-being and happiness. The inability to take control is seen as personal failure rather than stemming from wider social issues. Rather than being cynical about this, Fox’s work contains a sincere desire to effect change in herself in relation to others, her interest in the consciousness-raising techniques of second wave feminism equally inspiring the confessional chat show format of The O Show. Paradoxically though, the utopian and political urgency of this form of problem sharing, which in the 1970s entailed women coming together in groups to gain strength from one another’s experiences, has been co-opted by contemporary styles of management to encourage workers to be more productive. In fusing utopian and politically questionable ideals, Fox’s parodic staging walks a fine line between self-exploitation and the desire for self-autonomy.This could also be said of Hirsch’s work. For Illouz, in a climate in which emotional life is subject to rationalised public performances, authenticity is questionable. According to her, in earlier forms of capitalism the ‘subject could shift back and forth from the “strategic” to the purely “emotional”’.[21] However, in an era of psychology and the Internet ‘[a]ctors seem to be stuck, often against their will, in the strategic’.[22] For Illouz, the contemporary subject of capitalism is ‘increasingly split between a hyperrationality which has commodified and rationalised the self, and a private world increasingly dominated by self-generated fantasies’.[23]

However, in contemporary media, the evolution of the private sphere into a social declamatory-space of shared impersonations somewhat overrules Illouz’s split between public and private. Impersonations here are not the delusions of an authentic private self, though their iterative repetition is the very means by which something genuine may emerge whose transformative nature goes beyond the purely personal. Impersonation is acting. In a text on Fox’s work, curator Marianne Mulvey points out that Austin excluded acting from his study referring to it as hollow speech, incapable of sincerity.[24] However, as Mulvey argues, ‘[d]espite Austin’s claim that hollow speech acts cannot be taken seriously […] there is always the possibility of investing a belief in them, both as performer and audience’.[25] Trilling also refers to acting, specifically to Hegel’s reading of Diderot’s Rameau as an example of an inauthentic persona – ‘the buffoon […] the compulsive mimic without a self to be true to’ – whose impersonations in turn infect the spectator.[26] In today’s media contexts the impersonations of the buffoon are often championed as a true mirror of reality.[27] On the one hand one might see Hirsch’s and Fox’s feigning of confidence to acquire confidence as akin to the deceptive impersonations of the buffoon. However, the performative repetition of the statement ‘I am confident’ can also be said to be a creative action that opens the subject to risk and change.

Games of truth

Rob Horning’s discussion of performative truth-telling on social media in his online essay ‘Games of Truth’ is of interest here in relation to Hirsch’s and Fox’s performances of buffoonery. For Horning, critics of social media’s supposed inauthenticity mistake it as performance or ‘strategic’ playacting. He insists, citing Wayne Koestenbaum, that it can be a way of re-inscribing authenticity in a world that seems increasingly to be filled with fakeness. Key to his argument is that ‘as more behavior seems inauthentic and performative, there is a greater need to expose ourselves and have our own authenticity vindicated through the embarrassment this causes us’.[28] Horning aligns this method of exposure to the figure of the cynic as discussed by Foucault in his last two lecture series at the Collège de France in 1982-83 and 1983-84, published in English as The Government of Self and Others and The Courage of the Truth.

The cynic’s performance of truth-telling indexes the truth content of an utterance to the risk incurred in speaking it. Key to the cynic’s performance is the concept of Parrhesia or ‘free speech’, a plain-speaking truth marked by provocation. Coincidently, Foucault’s use of Parrhesia is one of Fox’s main theoretical inspirations, allowing her to avoid ‘seeking out some essential truth at the core of […] identity’. Acting as if she is confident allows her to become

someone I never thought I could be. I am also able to tell truths in this way without limiting my sense of myself to a single and limiting truth.[29]

While I am wary of applying an ancient Greek speech-act to the kinds of ‘truth-effects’ that might be generated in contemporary media, apposite here is Foucault’s account of the shift in the ‘parrhesiastic game’ from the classical Greek conception, in which the cynic courageously speaks the truth to the king, to ‘another truth game which now consists in being courageous enough to disclose the truth about oneself’.[30] This new kind of ‘parrhesiastic game’ is not a spontaneous outpouring of an authentic private self but requires practical training or exercises that are ‘concerned with endowing the individual with the preparation and the moral equipment that will permit him to fully confront the world in an ethical and rational manner’.[31]Although the training developed by the cynics in ancient Greece involves a much more long-term practice of self-scrutiny than that advocated in R.E.B.T., the continual corrective evaluation of situations using performative iterative techniques could be said to similarly enable more effective social behaviors.

Prior to considering Fox’s ‘parrhesiastic’ ethos in the light of Horning’s argument, I veered towards seeing Fox’s use of R.E.B.T.’s speech acts as being part and parcel of the management of emotional life that Illouz aligns with entrapment in cognitive capitalism. However, when linked to the parrhesiastic truth-telling of the cynic, Fox’s enactment of an authentic emotional life can be seen as a production of ritualistic social performances whose goals and risks cannot be predicted in advance. Rather than moving toward the ideological view of self-improvement for economic ends, the self here continually takes stock of how situations unfold in the present performative act, thereby revising future enactments of truth-telling. That said, the format of the artwork as chat show raises questions about the social capital required to effect transformative ‘truth-effects’. The online videos cut intermittently to a small art audience of about 20 people who are mostly seen smiling knowingly as if in on a secret rather than being open to risk and change.[32] The advantage of bringing Wearing’s Self-Made into the discussion at this point is not only that we get to witness the behind-the-scenes enactments of exercises/techniques normally invisible in a film or stage production, but that the participants come from walks of life in which professional autonomy is dependent on others to a much greater extent than for artists and corporate managers, who generally have greater autonomy over their actions.

Self Made shows how Method can produce ‘truth-effects’ that both mine and liberate core beliefs and habits by imaginatively inventing situations not dominated by market information and consumerist choice.In his guest appearance on The O Show Rumbelow describes Method as a technique that allows actors to relate to their characters by finding a truth in themselves, a sense memory, which can be tapped into to create said character. While this might suggest a core self, the point is that this sense memory can only emerge through training and thereafter it is put to use as a tool to create sincere impersonations rather than reproductions of a true self fixed in the past. Method reorients emotions in a neat inversion of R.E.B.T.’s emphasis on speech acts, but both engender new emotional affects that may circulate among subjects both performers and audience.

Fig. 3: Oriana Fox, The O Show: The Therapeutic Potential of Performance, 2012 (video still).Courtesy of the artist.

Self Made

Fig. 4: Gillian Wearing, Self Made, 2010, colour film with sound, 84 mins © Gillian Wearing, courtesy Maureen Paley, London; Tanya Bonakdar Gallery, New York; and Regen Projects, Los Angeles.

Self Made can be described as a documentary about the Method acting workshops undergone by the seven participants as training for their personal ‘end films’, five of which,straddling genres from theatre and television to more cinematic scenes, are included in the main film.[33] Underscoring itsuse of documentary conventions, the film includes a number of talking head sequences in which the participants introduce themselves – and more importantly, in which they comment on how they feel about their ‘end films’ after viewing them off-screen. Underlining the constructed nature of documentary (which to my mind is unnecessary in a media environment in which mainstream productions commonly use such‘alienating’ techniques), shots of the crew are inserted in a couple of sequences, one of which features Wearing directing a participant’s ‘end film’. Furthermore, the opening sequence shows the first part of participant Asheq Akhtar’s ‘end film’ which is shown again toward the end of the film, but this time using different camera angles and positions. This makes Self Made sound as if its goal is to reveal the mechanics behind the artifice, but I would argue it is an investment in the therapeutic dynamic of performance that can further elaborate the truth-effects of identity as a slippage between sincerity and authenticity.

Interestingly, for my purposes, Wearing describes the film as ‘search for authenticity in the dramatic moment, and the possibilities of creativity’.[34] Her first and only feature, the film reprises many elements of Wearing’s multimedia art practice informed by an interest in reality television and questions of documentary truth. To cast her earlier video Confess all on video. Don’t worry. You will be in disguise. Intrigued? Call Gillian (1994), Wearing placed an ad using the title of the proposed work in a magazine. For Self MadeWearing placed a similar ad in newspapers, job centres, and online. The ad, which appears onscreen in the opening moments of the film, reads: ‘Would you like to be in a film? You can play yourself or a fictional character. Call Gillian.’ Unlike the earlier work in which the participants wear masks while recounting tales of trauma, many of a sexual nature, in Self Made the seven respondents are undisguised, chosen, as Rumbelow continually reminds them, because they had interesting stories to tell. All wanted to explore some emotionally disturbing dynamic and get a perspective on it, e.g. issues of abandonment, violence, bullying, suicide. Participants are instructed in Method to enter into imaginary scenarios and play with their sense memories to find what Rumbelow advocates as their ‘truth’. This ‘truth’, or what I would call a ‘truth-effect’, is produced using relaxation techniques and role-play, the workshops acting as a kind of safe space that facilitates the emergence of buried emotions – not as they were in the past (there is no analysis here) but as they relate to the present task of generating transformative futures. Vital to this transformative potential is the fact that the participants’ ‘end films’ are self-invented narratives that construct scenarios in which they can act out unexplored elements of their psyches, things that they are afraid of and that keep them locked in certain behaviours. In this impetus, the method workshops can be aligned to ‘shame-attacking’ with the proviso that here it is through the putting into play of ‘sense-memory’ rather than through ‘plain-speaking’ that new impersonations can be developed to liberate stuck behaviours.

Fig. 5: Gillian Wearing, Self Made, 2010, colour film with sound, 84 mins © Gillian Wearing, courtesy Maureen Paley, London; Tanya Bonakdar Gallery, New York; and Regen Projects, Los Angeles.

In a workshop exploring the capacity to express anger, Rumbelow enables one of the participants, Lesley, to accept rather than hide her sadness. In response to her reluctantly admitting feeling sad after she has smashed a load of crockery against the wall in the workshop, he says ‘then that is the truth’. His direction gives her permission to unashamedly use this emotion in her ‘end film’ in which she stars as a 1940s heroine who rejects the attentions of an admiring man rather than trust him, although she longs for companionship both in ‘reality’ and in the ‘film’. The acting out of this desire, akin to the impetus of shame-attacking, allows her to see its impact on her life. This permission to accept oneself without judgement is taken to further degrees with character participant Asheq (or Ash as he is referred to in the film) whose breakdown into tears at various points in the film might lead one to assume that a cathartic outpouring of an authentic self is occurring. His talking head introduction of himself as an immigrant to Newcastlein the 1980s who suffered racial abuse as well as the domestic abuse issues that come up in the workshops suggest that this might be the case. Jenny Chamarette implies as much in her reading of his performance as stemming from ‘the difference of his experiences, as working class, as a self-defined immigrant, as an abused child’ although she is quick to acknowledge that his performance also enables spectators to ‘reflect on affect as a mode of exploring the creative power of difference’.[35] To my mind, Chamarette is alluding to two kinds of difference here, one being social difference, the other being difference as a creative act in which one’s social interpellationis exceeded. It is here that one becomes open to change.

In one of the workshop’s, Rumbelow directs the seven participants to visualise being immersed in tepid bathwater; they sway, eyes closed, on plastic chairs, generating the kinds of guttural sounds of ‘ah-ing’ and coughing-up that he has shown them previously. The visualisation brings Ash to his first breakdown. He chokes. Is this a glimpse of something real, the appearance of an authentic selfbeyond the impersonations of social discourse? The camera closes in, the film playing on the viewer’s curiosity. Rumbelow, like a shamanic therapist, places his hands on Ash’s shoulders while he continues to direct the group to relax deeper into the visualisation. After the session he asks his proverbial ‘what do you feel’ to which Ash responds‘I am very sad’. Again Rumbelow advocates staying with the truth of this feeling. This appears different to the R.E.B.T. reorientation of what would be perceived to be a negative feeling, however, this ‘sitting with an emotion’ opens up a space of self-scrutiny which works to good effect in Ash’s ‘end film’.

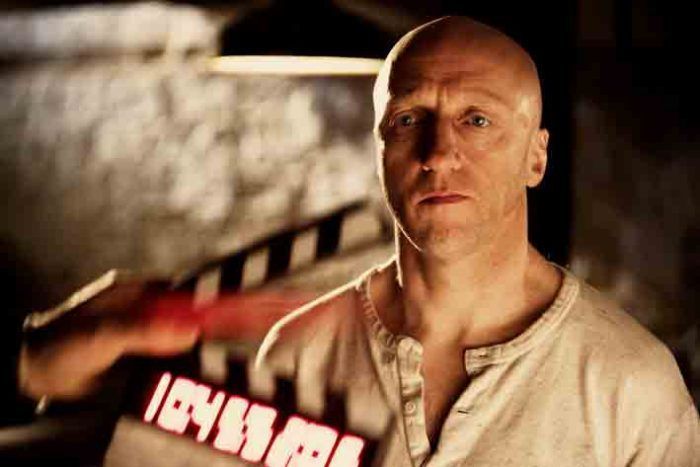

Fig. 6: Gillian Wearing, Self Made, 2010, colour film with sound, 84 mins © Gillian Wearing, courtesy Maureen Paley, London; Tanya Bonakdar Gallery, New York; and Regen Projects, Los Angeles.

Before training for this film, Ash speaks directly to the camera about his choice to play a role where he kicks a pregnant woman in the street and kills her baby. He says that this scenario is the worst he could imagine, implying that it has been suggested that he undertake such an exercise. Self Made, unlike observational documentary, is an extremely elliptical film, so the viewer has no access to the build up to his choice. As part of his training for the role, Ash has a one-to-one session with Rumbelow where he repeatedly kicks a pig carcass, Rumbelow encouraging him to situate his action in relation to past bodies he would have liked to hit. The imagined other as target of violence transforms the carcass into an object that can be used to act out the emotion in the present. Ash breaks down again. The initial feeling of enjoying his power over the carcass converts to feeling bad that he cannot feel remorse over his violence and the violent emotions he has imbibed from witnessing domestic abuse and being beaten by his stepfather as a child. The vulnerability of the documentary subject in their willing subjection to the camera’s interrogation is uncomfortable here, giving the viewer a vicarious proximity to another’s suffering, which is undoubtedly why Wearing intermittently highlights the constructed nature of the work. But paradoxically, this underscoring in Ash’s ‘end film’ engenders a circulation of sincerity beyond the volitional subject in that it exposes how the training of the emotions generates the self-scrutiny to enable personal, and perhaps social, change.

In his ‘end film’, Ash was again having difficulty channelling the remorse he thought he should feel after hitting a pregnant woman, the sonic impact of which shocks the viewer’s senses much as the moral idea itself is abhorrent – but it is the case that these desires exist and are acted out in society. By repeating them in a staged context, Ash is unwittingly engaging in a form of critique in which art mimics ‘reality’ both to show its injurious nature and to liberate the self from an unreflective acting out. It is here that the therapeutic dynamic of the scene lies rather than in Ash’s action being the outpouring of pent-up aggression. Rounding the corner after his violent action, he attempts to cry but eventually calls a halt to the filming, upset that he cannot feel the remorse appropriate to the injurious nature of the act. The crew and cameras are shown on-screen. Rumbelow is called to the scene to help Ash reconnect with the emotional places they explored in the workshops. Reiterating this role-play enables him to act sincerely and feel the requisite emotion. For the viewer, this glimpse of the technique being put into operation is fascinating because the display that it is a construction does not destroy its ‘truth-effect’, i.e. the sense that a sincere feeling of remorse is produced through artifice. In Ash’s post-film interview, although he is shocked by the literal nature of his on-screen violence, he says that Method gave him the training to get the task done. The ‘truth-effect’, which bypasses the ideology of emotion that would naturalise it as an authentic outpouring of a volitional subject, happens in two worlds at the same time, the fictive world of the film and the psychic world of Ash’s processing of the emotion in a slippage between sincerity and (in)authenticity. Taking a Deleuzian approach to this film, David Deamer reaches a similar conclusion saying that in relation to the participants and their characters ‘[w]e have not reached some inner truth. They have gone out of themselves, made new connections, false truths’.[36] This kind of Deleuzian-inspired depersonalisation of emotion exceeds one’s interpellation as a raced, classed, and/or gendered subject and enhances one’s capacity to perform and reflect on potential selves so as to enable the transformation of negative social feelings beyond oneself.[37]

This can be further highlighted by contrasting Ash’s post ‘end film’ reflections to another of the participants’. Lian, who coincidently looks like Wearing, had acted out a theatrical scene from Shakespeare’s King Lear in which his daughter, Cordelia, challenges and confronts her father, the scene being analogous to abandonment issues Lian had with her father. Her ‘end film’ is compelling. However, Wearing frames her in her post ‘end film’ reflection standing behind the window inside her flat wistfully looking out, as her voiceover states that now things are better between herself and her father. She is then shown speaking direct-to-camera affirming that now ‘I know he loves me’ and ‘he texts us every day’. Lian’s sense of self-recovery fits with the naturalising of emotions in which sincerity is professed as an integration of a unified self, rather than a facility to produce new impersonations. Lian’s sincerity contains no irony, whereas Ash’s slippage between authenticity and sincerity in his use of techniques suggests the possibility of a freedom to engage in acts of self scrutiny which have a less predictable outcome. Method as technique enables Ash to distribute his fictive, real, and imagined selves in scenarios in which ‘actors’, e.g. Ash’s mother and stepfather, do not always remain locked in the same places.

Conclusion

Method and R.E.B.T. are technical systems which can be put to work to execute performances of identity which operate fluidly between both axes of sincerity, its inner state and outer surface, not to conjoin them in an authentic integrated whole, but to push them beyond the personal expression of a self. Although the alignment of R.E.B.T. with the quick fix solutions of problems that ignore social determination makes it politically suspect, both techniques are interesting from the viewpoint of an aesthetic whose goal is an art of living. In a post-postmodern age, in which ‘sincerity has become a media effect’, the issue of sincerity is no longer one of ‘“being” sincere but of “doing” sincerity’.[38] Both The O Show and Self Made could be said to ‘do’ sincerity in this sense, i.e. producing it through communal speech and/or technical acts that entail a creative leap of faith into an unpredictable future. Rather than the aforementioned ‘loss of personal integrity and dignity entailed by impersonations of social existence’, in our era distinctions between an alienated authenticity and the impersonations of sincerity through cliché and hollow speech have collapsed. Through the erosion of public and private spheres via technology as a social declamatory space, the previously private sphere of authentic soul searching is opened to the sharing of impersonations. Paradoxically, it is the circulation of these impersonations that engenders a new sincerity, one which is heartfelt and genuine, albeit peppered with a necessary irony. It is here that Fox’s recuperation of sincerity in acts of laughter and Wearing’s exposure of it in acts of tears can be placed.

Author

Dr. Maria Walsh is Reader in Artists’ Moving Image at Chelsea College of Arts. She is an Associate Editor of the peer-reviewed journal MIRAJ (Moving Image Review and Art Journal) and was Guest Editor of the ‘Feminisms’ double issue which included her article ‘From Critique to Resistance to Autonomy: Alex Bag Meets Ann Hirsch’. Other peer-reviewed articles on film philosophy, independent cinema, and artists’ moving image have appeared in Rhizomes, Angelaki, Screen, and Refractory. Her monograph Art and Psychoanalysis was published in November 2012 with I.B. Tauris and she is currently working on a monograph on performative therapeutics in artists’ moving image.

References

Archey, K. ‘Artist profile: Ann Hirsch’, Rhizome, 2012: http://rhizome.org/editorial/2012/mar/7/artist-profile/ (accessed on 19 October 2015).

Austin, J.L. How to do things with words: The William James lectures delivered at Harvard University in 1955, edited by M. Sbisà and J.O. Urmson. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1976.

Biressi, A. and Nunn, H. Reality TV: Realism and revelation. London: Wallflower, 2005.

Butler, J. Gender trouble: Feminism and the subversion of identity. London-New York: Routledge, 1999.

_____. Bodies that matter: On the discursive limits of “sex”. London-New York: Routledge, 1993.

Chamarette, J. ‘The “New” Experimentalism? Women In/And/On Film’inFeminisms: Diversity, difference and multiplicity in contemporary film cultures, edited by L. Mulvey and A. Backman Rogers. Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press, 2015: 125-140.

Deamer, D. ‘Now You See Me…Gillian Wearing’s Self Made’ in Gillian Wearing, edited by D. Globus, D. Hermann, and D. Krystof. London-Dusseldorf: Whitechapel Gallery/Ridinghouse/Kunstsammlung/Nordhein-Westfalen, 2012: 39-45.

Foster, H. ‘Obscene, Abject, Traumatic’, October, Vol. 78, Autumn 1996: 106-124.

Foucault, M. ‘Truth and Power’ in The Foucault reader, edited by P. Rabinow, interview with A. Fontana and P. Pasquino. New York: Pantheon, 1984: 51-75.

Fox, O. ‘Introducing The O Show’, 30 May 2012: http://www.thisisperformancematters.co.uk/potentials-of-performance/words-and-images.post125.html (accessed on 23 June 2016).

Froggatt, W. ‘A Brief Introduction To Rational Emotive Behaviour Therapy’, February 2005: http://www.rational.org.nz/prof-docs/Intro-REBT.pdf (accessed on 23 October 2016).

Furedi, F. Therapy culture: Cultivating vulnerability in an uncertain age. London: Routledge, 2004.

Hirsch, A. ‘gURLS Performance Text’: http://therealannhirsch.com/writing/gurls/ (accessed on 9 December 2016).

Horning, R. ‘Games of Truth’, The New Inquiry, 3 November 2013: http://thenewinquiry.com/blogs/marginal-utility/games-of-truth/ (accessed on 15 September 2015).

Illouz, E. Cold intimacies: The making of emotional capitalism. Cambridge: Polity, 2007.

Kelly, A. ‘Dialectic of Sincerity: Lionel Trilling and David Foster Wallace’, Post45, 17 October 2014: http://post45.research.yale.edu/2014/10/dialectic-of-sincerity-lionel-trilling-and-david-foster-wallace/#identifier_52_5365 (accessed on 9 October 2016).

Morley, P. ‘Back to Reality’ in Gillian Wearing: Family history: View from my bedroom window, edited by S. Bode. London: Film & Video Umbrella and Maureen Paley (Gallery), 2007: unpaginated.

Mulvey, M. ‘Is There Sincerity in Hollow Speech? Feeling the Cliché in Contemporary Performance’, NOWISHERE Contemporary Art Magazine, no. 3 (n.d.): 16-21.

Pearson, J (ed.). ‘Discourse and Truth: The Problematization of Parrhesia. 6 Lectures given by Michel Foucault at the University of California at Berkeley, Oct-Nov. 1983’, 1985: http://www.foucault.info/system/files/pdf/DiscourseAndTruth_MichelFoucault_1983_0.pdf (accessed on 1 November 2016).

Rottenberg, C. ‘The Rise of Neoliberal Feminism’, Cultural Studies, 28, no. 3, 2014: 418-437.

Trilling, L. Sincerity and authenticity. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1972.

Van Alphen, E. and Bal, M. ‘Introduction’ in The rhetoric of sincerity, edited by E. van Alphen, M. Bal, and C. Smith. Stanford: Stanford University Press, 2009: 1-18.

Walsh, M. ‘Performing Resistance to Performing Autonomy and Back Again: Alex Bag Meets Ann Hirsch’, MIRAJ: Moving Image Review and Art Journal, vol. 4:1 & 2, 2016: 13-41.

Wearing, G. http://selfmade.org.uk/gillian/ (accessed on 3 April 2017).

[1] Trilling 1972, p.31.

[2] Ibid, p. 9.

[3] See Biressi & Nunn, 2005, p. 104.

[4] Kelly goes on to discuss the personal liberation that results from the repetition of Alcoholic Association mantras for the characters in David Foster Wallace’s Infinite Jest in a manner that is not unlike Judith Butler’s earlier discussions of performativity in which ritualistic repetition is key to the resignification of norms (Butler 1996).

[5] Van Alphen & Bal 2009, p. 5.

[6] Trilling 1972, p. 2.

[7] Van Alphen & Bal 2009, p. 3.

[8] Ibid.

[9] Foucault in Rabinow 1984, p. 73.

[10] Trilling 1972, p. 43.

[11] See Furedi 2004, pp. 84-105.

[12] Butler 1993, p. 96.

[13] Fox, 30 May 2012.

[14] Email correspondence between the author and Fox, 27 October 2016.

[15] Hirsch, ‘gURLS Performance Text’, n.d. In an email correspondence between Fox and the author Fox notes the common ground between her work and Hirsch’s in this respect. For a more detailed analysis of performativity in Scandalicious, see my article ‘Performing Resistance to Performing Autonomy and Back Again: Alex Bag Meets Ann Hirsch’, MIRAJ: Moving Image Review and Art Journal, vol. 4:1 & 2, 2016: 13-41.

[16] Hirsch in Archey 2012.

[17] Froggatt 2005, p. 2.

[18] See Foster 1996.

[19] See Furedi 2004, p. 4.

[20] Illouz 2007, p. 38.

[21] Ibid., p. 110.

[22] Ibid., p. 111.

[23] Ibid., p. 113.

[24] Mulvey, n.d., p. 17.See Austin 1976, p. 22 for more detail.

[25] Mulvey, p. 17.

[26] Trilling 1972, p. 44.

[27] One could name many television shows here, but Paul Morley’s reference to Russell Brand on a ‘Big Brother’ chat show as a ‘Byronic buffoon’ seems particularly apt (Morley in Wearing 2007, unpaginated).

[28] Horning, 3 November 2013.

[29] Email correspondence between the author and Fox, 27 October 2016.

[30] Foucault in Pearson 1985, p. 55.

[31] Ibid., p. 58.

[32] Interestingly,an audience member hired Ainsworth as her personal therapist after the performance.

[33] The other two participants’ ‘end films’ were not included in the film but are in the DVD extras.

[34] Wearing 2017.

[35] Chamarette 2015, p. 139.

[36] Deamer 2012, p. 44, italics mine.

[37] Interestingly, Ash continued to attend Rumbelow’s Method acting workshops after the film.

[38] Van Alphen & Bal 2009, p. 16.