Truth and truths-to-come: Investigating viral rumors in ‘Q: Into the Storm’

by Renée Pastel & Michael Dalebout

In a podcast interview the day after the finale of Q: Into the Storm (HBO, 2021), Jim Watkins, then owner of the online forum 8chan, and his son Ron Watkins, the site’s then administrator, suggested that the docuseries director, Cullen Hoback, was himself Q.[1] Hoback’s docuseries about Q, the shady figure behind the conspiracy that shook mainstream American politics during the Trump administration, premiered just two and a half months after the January 6 attack on the US Capitol. The series purports to offer a ‘crash course’ for a mainstream audience in understanding QAnon followers, who believe in an individual or in individuals purporting to have high-level federal security clearance. Q’s posts on 8chan included provocative questions and Nostradamus-esque clues about a global cabal of sex-trafficking pedophile politicians who truly run the world. The violent attempt to intervene in the certification of President-elect Joe Biden’s electoral victory was imagined by many, especially Q-believers, as a catalyst to ‘the storm’, the period during which a corrupt world order would face its reckoning. For QAnon adherents, Q is a liaison between them and former President Donald Trump, framed by Q to be the heroic figure who would lock up and execute those politicians. In Hoback’s Storm, however, Q is unmasked as Ron Watkins: private computer nerd turned public voting skeptic and ‘cynic who treats the whole world like it’s a game’.

Q: Into the Storm (Storm here onwards) presents itself as a non-fiction recording of reality. It documents the ins, outs, and history of QAnon as the phenomenon unfolds, ultimately organised around the question ‘Who is Q?’, which serves as a narrative tether. Hoback thematises within six episodes his efforts as a documentarian not to simply record the truth, but to make the truth speak itself. Notwithstanding the fact that some Q-believers say that Q’s identity is less relevant than the movement itself,[2] Hoback’s inquiry holds high stakes. Revealing the high-ranking official Q claims to be would ground the QAnon narrative, legitimising it. Conversely, revealing anyone else would delegitimise Q’s ‘insider’ status, undercutting the authoritative intel feeding the QAnon movement.

It seems obvious, therefore, that Hoback would adopt an investigative journalistic approach, creating a docuseries that mirrors true-crime podcasts and Netflix-era series. In this article, we further define this popular mode, emphasising the investigative docuseries relationship with the documentary tradition of re/presenting the truth (or the place where the truth ought to be).[3] At the same time, we pose that what Storm documents is Hoback’s own entry into the gamified world built by Q’s activities on 4chan and 8chan and is itself a move within that game.

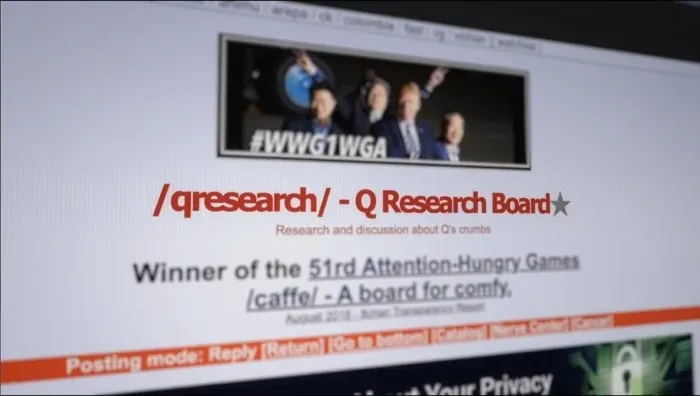

Fig. 1: 8chan’s QResearch board.

Storm diverges from mainstream journalistic practices, which carefully frame any Q theories in terms of their errant reasoning by entering into the same sort of associative, interpretive framework through which Q-theories interrogate the world. We consider Storm first in terms of the investigative mode of documedia (broadly encompassing non-fiction podcasts, docuseries, and documentaries, especially recent true-crime offerings) and then in terms of alternate reality games (ARGs). The investigative mode focuses on telling stories that inevitably reveal some truth that was initially missed, even if unconfirmed, partial or speculative. Similarly, conspiracy theories are founded on a mirror image of such investigations, focused on inevitably displaced revelations, which have not yet transpired. Storm provides an exemplary case study through which to consider the role contemporary documedia play in cultivating, augmenting, or fortifying the ways people make sense of their realities together. Ultimately, we argue that Hoback’s docuseries clouds an important distinction between truth and truth-to-come that is already hazy in conspiratorial thinking.

Relying on familiarity with investigative documedia, Storm exemplifies the mode of such media, which engage with their subjects by entering into their logics – in this case, gamified conspiratorial thinking. Investigation, like conspiratorial thinking, shares a desire to bring people onto ‘the same page’. In a post-truth era in which truth claims are destabilised and digital media’s indexicality is questioned, traditional methods of collecting evidence and eyewitness testimony are no longer taken to produce even the semblance of common truth.[4] Instead, the investigation itself grounds collective interaction. While many critical responses to Storm question whether the docuseries successfully uses the tools of QAnon to counter its sway, our driving question is instead the extent to which Hoback’s docu-performance transforms conspiracy thinking by practicing it. Our discussion of rumors examines how their circulation, both online and in Storm, forms ways of thinking that serve as bases of knowledge.

Seeking common ground

At its core, QAnon traffics in rumors, both about what is going on in the world and who is giving clues to some ‘more real’ actuality. Hoback is extremely successful in forging relationships with key players deeply involved in QAnon – whether vocal Q supporters, such as QTubers who stream on YouTube and Facebook, or technical admins usually behind the scenes, including Ron Watkins and his father Jim, or Fredrick Brennan, who created 8chan. In sitting down with varied interviewees to trace the origins of QAnon, many of whom offer contradictory accounts, Hoback takes interpersonal intrigue seriously. Sebastian Jobs discusses the importance of tracing rumors and embracing historical uncertainty, arguing: ‘rumors and gossip give us the chance to historicize the panorama of subjective perspectives, contextualize the rumor-mongering and give room to the voices of the many in these stories, even if it means that they contradict each other’.[5] Hoback solicits the rumors swirling among Q-followers earnestly – researching and following each lead, tracing the lineage of websites and the web of uncertainties on the promise that these rumors eventually lead the way to the person(s) behind them all. As a result, Storm produces a revealing and intriguing picture of how QAnon becomes what it is.

Widely regarded to be a conspiracy theory, QAnon encourages conspiratorial thinking by asking its believers to do their own research, primarily on those websites that trade in rumors. Rumors and conspiracy theories overlap in what Jill Edy and Erin Risley-Baird term ‘rumor communities’. As they argue, ‘rumoring involves not an individual, psychological predisposition to spread misinformation, but a shared need for understanding and support and a common construal of the social world’.[6] Searching for common ground and community essentially reframes thought around conspiracy theories and rumors: whereas traditional conspiracy theory scholarship tends to focus on the psychological susceptibility of individual believers, considerations of rumors focus on community building.[7] Nicholas DiFonzo notes, ‘using the rumor framework leads us to see conspiracy theories as part of a social system of interacting persons’. So framed, conspiracy theories appear ‘as stories that are communicated between people in relationships and as stories that grow out of the hub-bub of the group’.[8] In this vein, rather than debunking what is said as an effort to contain conspiratorial thought, Hoback uses his docuseries to map the contours of belief, tracing out each thread of the web of rumors in his search to find Q, from whom this form of conspiracy thinking spins.[9]

Considered in terms of rumor communities, Hoback’s approach to documenting QAnon in Storm becomes clear. He accepts the storytelling frameworks that unite the varied interview subjects, encouraging them to share their thought processes, and edits the final docuseries so as to redouble the repetitions and patterns that appear across interviewees. It is worth noting that this approach draws upon a tradition of more recent documentaries delineated by Stella Bruzzi as performative, drawing upon the work of J. L. Austin: ‘the enactment of the notion that a documentary only comes into being as it is performed, that although its factual basis (or document) can pre-date any recording or representation of it, the film itself is necessarily performative because it is given meaning by the interaction between performance and reality’.[10] Hoback’s documentarian process is akin in practice to QAnon followers ‘doing their research’, as it synthesises a field of multiple perspectives into a coherent, filmic order. We approach Hoback’s documentary process similarly – not just as a story about QAnon, but a story from within QAnon, about doing research and the effects of that research.

Unlike rumors underpinning the Q narrative, however, Storm is a popular, mass-media object that circulates in stand-alone form – the externalised memory of Hoback’s participation in a conspiratorial world. As such, we consider the docuseries in light of philosopher Bernard Stiegler’s reflections on audiovisual media (especially cinema) as an ‘industrialization of memory’. Stiegler writes,

The 20th century is the century of industrialization, the conservation and transmission – that is, the selection – of memory. This industrialization becomes concretized in the generalization of the production of industrial temporal objects (phonograms, films, radio and television programs, etc), with the consequences to be drawn concerning the fact that millions, hundreds of millions of consciousnesses are every day the consciousnesses, at the same time of the same temporal objects.[11]

Stiegler’s ‘consciousness’ enfolds both perception and imagination. For phenomenologist Edmund Husserl, perception is our present experience of encountering the world as it rushes at us, and the primary form of memory. Imagination is memory’s secondary form, the storehouse of conceptions and experiences we draw upon when making sense of our world. But whereas Husserl splits perception and imagination into distinct, even opposed, phenomena, in Stiegler’s philosophy, they are entangled. Our imagination informs our perceptions, shaping how and what people see and hear. Even more, Stiegler’s account includes a third form of memory: technical artifacts, especially media objects, that intervene in our imaginations.

Consequently, contemporary media do more than facilitate the distribution of narratives about the world. Media also inform how those narratives unfold by shaping not what people know but how they think. For Stiegler, audiovisual media are particularly influential; he emphasises that ‘consciousness functions just like cinema, which has enabled cinema (and television) to take it over’.[12] His point is not that film seduces or infiltrates people. Rather, that people think about the world and relate themselves to it and each other by drawing on the media ecology around them. The narratives trafficked today in cinema and online streaming platforms spread exteriorised memories through public life that enable and constrain how we imagine and perceive our shared world. Ben Roberts puts it this way: ‘the industrialization of memory shifts this loss of individuation to the psychic domain’.[13] Said differently, the increasingly homogenised narratives limit how people shape themselves, turning them away from worlds specific and local to them, and thereby constricting the particularity of their own consciousnesses.

What matters is the automaticity of people’s consciousness in internalising exterior frameworks of thinking, and not the content of that consciousness (e.g., narratives). The reduction of ways of thinking about the world ‘results in what [Stiegler] calls a “proletarianization” of the spirit or “pauperization of culture”’,[14] a collective reduction of ways of knowing, narrating, and experiencing. This reduction leads to the social condition that Stiegler refers to as being herd-like.[15] In Storm, Hoback mirrors QAnon followers, attempting to confront and intervene in people’s apparent slumber. The Q-believers seem to earnestly take up media anew to jolt others awake to a way of thinking that reveals the evils they believe run the world, and Hoback does the same, albeit to cast light onto the shadowy figure(s) behind QAnon.

Does Hoback’s Storm docuseries as externalised memory contribute to or intervene in the industrialisation of consciousness that led to the January 6 ‘Storm’? In the following two sections, we differentiate two modes of interacting with the world as they appear in Storm, the first that of investigative documedia and the second that of participatory transmedia gameplay. Rather than prioritise either, we analytically distinguish them and show how their interaction results in a unique cinematic object that tasks itself with simultaneously informing and intervening in the social fabric of American life.

This is not a game: The investigative mode in Storm

The very first shot of Storm animates the text of a ‘Q-drop’, a post from Q on an anonymous message board. The words quickly appear across the screen as if typed in real time:

>>Drop 885 (Mar 8 2018)

Everything has meaning.

This is not a game.

Learn to play the game.

Q

Fig. 2: Drop 885.

Q-drops typically consist of leading questions that reinforce the conspiracy about a global cabal of pedophile politicians, and serve as calls to action to Q’s followers – especially the Anons on 8chan – to investigate and put the pieces together. From this opening, the investigative mode (and its conspiratorial thinking mirror image) is twinned with a game play mode of thinking. This opening ends with a fast montage, beginning with The New Yorker footage of the January 6 storming of the Capitol and ending with a rapid-fire set of images of the letter Q on T-shirts, memes, and signs, all while Hoback’s narrative voiceover intones: ‘And while a shocked nation searched for answers, to me, it seemed like an inevitable conclusion to an absurd and almost unbelievable story.’ Thus, Hoback structures his docuseries as an investigation, not to answer the questions of what happened or how it could have happened, but to identify the anonymous figure widely credited with inspiring that day’s events.

Simultaneously, Hoback acts as a performer-author.[16] By thematising himself within the docuseries, he shapes the story. In the first episode, he notes that he began gathering footage about QAnon in 2018, seeing it at that time as defining ‘the frontlines’ of free speech battles. His narration credits free speech online as both a driving motive for making the series and a means to successfully counteract Q:

And even though I don’t believe that Hillary Clinton eats babies, I also wasn’t convinced that silencing Q’s followers was the right idea, either. Q derives its power from anonymity. […]. So I set out to chart Q’s origins and meet the players in order to understand the underlying motives…. It seemed unmasking Q might bring an end to what in 2018 was still mostly a game.

From this start, the series is set to explore QAnon in terms of issues of free speech online, which Hoback claimed was the purported driving impetus for the owners of 8chan to maintain the sole site on which Q posted. It seemed to Hoback that the best way to find Q was to meet the people who buttressed Q’s online existence beyond Q’s most outspoken supporters.

Thus structured as an investigation, the series spends the first two episodes bringing the audience up to speed on the topography of QAnon online, while recounting the lineage of anonymous platforms that led to those Q used. Having introduced many of the ‘players’ in these first two episodes, including QTubers, their followers, Frederick Brennan (8chan’s creator), and Jim and Ron Watkins (who bought 8chan, later rebranded 8kun), Hoback follows the various threads and theories they put forward about one another and about Q, seeking to find Q and stable ground in the seemingly endless morass. On the surface, this is a typical investigative docuseries – looking for flaws in accepted knowledge, following up on theories offered, and soliciting views from a range of witnesses. Yet more unusually, Hoback centers himself among the players, and lingers extensively on his personal relationships with those he deems to have the most potential insight into Q’s identity: those who designed and run the websites offering Q space to post. The conversations that make the final cut of the docuseries range from cagey and dodgy remarks about Q to seemingly banal exchanges about their lives and hobbies. The interviewees clearly feel comfortable with Hoback; the conversations are often gossipy and full of crass jokes and speculation, perversely keeping the viewer on the hook, awaiting the payoff.

Fig. 3: Cullen Hoback and Jim Watkins on Jan. 6.

Considering that Storm falls under the purview of HBO Documentary Films, it is worth flagging the potential discrepancy between audience expectations of objectivity in documentary media and the range of documentary approaches that problematise the divide between objectivity and subjectivity in documenting events. ‘Investigative docuseries’, a recognisable and popularly used descriptor for such series, lacks an authoritative scholarly definition. The term draws from the overlapping traditions of investigative journalism and documentary series. Cousin to investigative series with a more journalistic bent, contemporary investigative docuseries superficially share investigative journalism’s guiding principle of ‘exposing to the public matters that are concealed – either deliberately by someone in a position of power, or accidentally, behind a chaotic mass of facts and circumstances that obscure understanding’.[17] Investigative docuseries, however, have a further potential flexibility in the mode of presentation of their findings than investigative journalism, which tends to stick to ‘objectively true material’.[18]

Within the realm of documentary theory, much debate centers around the blurring of fact and fiction – whether with regard to reenactments, the haziness of memory, or issues around the constructed nature of any filmic project. Dirk Eitzen provocatively proposes that documentary may sit closer to gossip than news, a proposal that he notes is complicated by the weight of ever-present expectations of documentary truth.[19] ‘Documentaries do not trade in facts in the same way that news is supposed to’, he explains. ‘Like news, they refer to and represent situations and events that are supposed to be real, but their power to engage and affect us revolves around social appeals not factual information.’[20] Such appeals are often affective, functioning via formal elements, such as editing juxtapositions, emotionally charged musical scores, and shot angles, to make an audience feel superior, observant, apprised, or otherwise prepared to face the world. Of course, these are the very aspects of documentary production that conflict with Bill Nichols’ inclusion of documentary within his constellation of ‘discourses of sobriety’, nonfiction systems that can have an impact on the world, presumably with their direct relation to reality[21] – but simultaneously, Nichols’ theoretical framework still informs a popular audience’s imagination of the documentary form.

A more interesting aspect of an investigative docuseries such as Storm is the constructedness required for the serial format. Not only is each episode meant to have a self-contained form, the series as a whole needs an arc. This means that no matter how convincingly the documentarian produces episodic suspense to drive the series, thereby creating a feeling for the audience that they are making discoveries alongside the filmmaker, the filmmaker nevertheless knows the ending. The audience does not: ‘Texts know more than they tell at any one moment.’ Nichols adds, ‘They can be straightforward or elusive in relaying that information.’[22] In the case of Storm, the series from the start avows that it will reveal the truth of QAnon by unmasking Q, and give a ground to the seemingly bottomless set of beliefs espoused by Q and held in faith by Q’s followers. The docuseries was a unique temporal object. Though a document of past events, it informed an ongoing present promising to clarify – especially for individuals outside of QAnon – the thrall of a movement whose truths-to-come remained to-come. Seen in a genealogical lineage with investigative documentaries like Errol Morris’s The Thin Blue Line (1988) and documentary podcasts like Sarah Koenig and Julie Snyder’s Serial (2014-), Hoback’s Stormrelies on its viewers’ familiarity with an investigative tradition that requires some patience before the truth is revealed – the initial building and gathering of information is what permits the truth to come out, and to stand as truth.

That documentary media necessarily delay any revelation of truth until their end (though they know it from the beginning) suggests a surface-level mirroring between the investigative mode and conspiracy theorising. Discussing the shared aspects of news journalists and conspiracy theorists in service of a larger point about documentary media in the age of ‘fake news’, Kris Fallon notes, ‘it is more accurate to claim that communities in the thrall of conspiracy theorizing know a great many things, even if what they collectively know is (by definition) mostly incorrect’.[23] In creating his investigation, Hoback follows every potential lead given by those who support (technically or faithfully) Q. In practice, this means taking each proffered idea at face value without distinguishing its situated validity, all in service of the unmasking, the truth-to-come. That Hoback ignores the journalistic strategies for reporting on burgeoning conspiracy theories was one of the main concerns in pre-reviews and critiques of the docuseries alike:

There are best practices for reporting on conspiracy theories in general, and QAnon in particular. Into the Storm flouts all of them. It names and profiles influencers who sprout like weeds in the light of attention; it serves up ardent Q followers as figures of ridicule; it rarely pauses to debunk the most outlandish beliefs it details, assuming – maybe – that viewers at home can do that for themselves.[24]

In Storm, the investigative mode often blurs into conspiratorial thinking. Not necessarily by accepting the conspiracy theories floated by QTubers and followers, but rather by embodying some of their underlying thought patterns in the editing of Hoback’s investigation. Hoback cautions from episode one that ‘QAnon creeps into your thoughts, it changes the lens through which you see the world.’ Hoback’s investigation mirrors conspiratorial thought most notably in following associative loops between people and events, repetitions of questions, symbols, and speculations, and the guiding assertion that there are no coincidences. As Bruzzi characterises it, ‘The chain (one element leading to the next until the filmmaker gets close to his or her main subject)’ is a ‘fundamental characteristic’ of investigative documentary.[25] The chain that Hoback builds in Storm, however, is a twisty chain of loopbacks and missed connections from its beginning.

Hoback’s framework for unmasking Q in Storm poses an analytic challenge because it is necessarily an investigation into rumors, often rumors motivated by people with competing interests. Yet Hoback begins the series oddly, with a cagey conversation about QAnon between an unidentified Ron Watkins and his neighbors. The only information given is that the conversation occurs in Sapporo, Japan in November 2019. Hoback appears in this conversation, framed without showing his face, in order to show a Q-drop to the male neighbor. This interchange ends with the reveal that the still-unnamed Watkins runs 8chan, and a cut to the outside of the house, as Watkins questions,

Everyone likes free speech. But there’s a tipping point for everybody. When is free speech too much?

The episode then cuts from idyllic wide shots of Japanese countryside to coverage of the January 6 attack on the Capitol, as if to suggest it is the answer. This opening is striking for its divergence from the norms it sets up in the rest of the episode: individuals are identified the first time they speak, for example. But it is also a telling moment of withholding information – information in this case that is important for the series arc as a whole. Ron Watkins as engineer of 8chan begins and ends the series, and it is he who Hoback believes to have unmasked as Q. By the time Watkins is finally identified (also as CodeMonkeyZ), the audience has seen him in many quickly edited montages but has likely forgotten this opening in Hoback’s deluge of images and information.

As such, instead of documenting a found truth, as one expects of documentary film, in Storm, Hoback uses the documentary mode to cajole or construct a truth. The QAnon phenomenon is predicated on the inevitable but always delayed truth-to-come; Storm attempts to short-circuit the prophetic guarantee that fuels the conspiracy by taking its prophet out of the shadows, empowering him/her. It is, in other words, a move in a game, the game of QAnon that the miniseries frequently acknowledges, notably in the opening title of episode one and in episode five, ‘Game Over’. Because Hoback (perhaps necessarily) does not thematise Storm as part of this game, however, viewers are likely to take the docuseries as a straightforward exposé neither recognising nor learning from the moves he makes to ward off conspiratorial thinking. Nevertheless, as he tracks Q’s patterns, he chooses visual and aural repetitions in his own re-creation of his investigation, such as the adoption of ‘red pill’ from The Matrix film franchise in the opening credit sequence, which symbolizes an awakening to the truth for QAnon adherents. By iterating the nomenclature of Q-followers, Hoback crafts something that upon deeper reflection looks less like an investigation in the mode of investigative journalism and increasingly like gameplay.

Learn to play the game: The participatory transmedia mode in Storm

Q Drop 885 (discussed above) also flags that Hoback qua skilled documentarian cannot just investigate the truth. Its second and third lines, ‘This is not a game/Learn to play the game’, affiliate Storm with the media genre of ARGs. Discussing Dave Szulborski’s 2005 book This Is Not a Game, game scholar Alenda Chang writes, ‘ARGs tap the inherent power of good storytelling along with the simultaneous instantaneity and anonymity of the internet and related communication forms – text messaging, instant messaging/live chat, email, websites, video clips, phone calls, even discoverable crafted artifacts – in order to engage participants in play that is seemingly not play.’[26] ‘Play that is seemingly not play’ itself is a distillation of ARG game design. ARGs use the real world as the setting for transmedia stories facilitated by the game designers, or ‘puppet-masters’, and altered by their players. ARG players search for and share information that advances plot possibilities put in place by the puppet-masters. Players locate ‘trailheads’ in the real world, such as websites or videos, that serve as ‘rabbit holes’ into a given ARG’s narrative. Hiding behind ‘the curtain’, puppet-masters interact anonymously with players, implementing new artifacts and clues within the game itself. Hoback’s ostensive inquiry into the identity of Q entangles Storm with the game itself.

Scholars and journalists alike recognise ways the QAnon movement functions as an ARG.[27] ARGs ‘take the player on a scavenger hunt in search of more information and clues to cracking a code’, Joshua Clements writes. ‘In similar fashion, QAnon’s followers use the Internet’s limitless information and search functions to discover and create new meanings for current events.’[28] In episode one of Storm, Hoback explains how Q-drops are the beating heart of QAnon. Following a Q-drop, Q-followers on 8chan (Anons) scour the internet looking for associative links between Q’s clues and real-world events. They then post the results of these searches, or ‘digs’, on the boards, where other Anons with more expertise sift through them. These ‘bakers’ select the most viable ‘breadcrumbs’ from the digs in order to ‘bake’, or produce, an interpretation that possibly decodes the Q-drop. The bakers’ interpretations are validated when Q references them in subsequent Q-drops. Effectively, Q advances the QAnon story by recourse to the activities of the players as ARG puppet-masters do.

As such, what appears as Hoback’s investigation into the identity of Q doubles as an effort to reveal QAnon and the Q narrative as an ARG. Though some mainstream ARGs avow that they are games, most ‘disguise the fact that they are games, attempting to blend into players’ real daily activities in a seamless fashion by using media and communication devices… that players already routinely use in the course of their normal lives’.[29] Read this way, Hoback is playing the game, a claim that is difficult to confirm because he does not avow that he is doing so, which in turn is part of playing an ARG – apparently even when breaking it. Nevertheless, there are clues he is doing so. Hoback seemingly appropriates the final line of the opening Q-drop, ‘Learn to play the game’, over the series arc, training his audience to understand what QAnon is in episodes one and two as a background for developing a counternarrative about Ron Watkins as Q that thereby breaks the game. Though Hoback does not address ARGs in Storm, his interviewees dismiss the idea that QAnon is a LARP, or Live-Action Role-Playing Game.[30] As with ARGs, LARPs take place within real-world environments, but LARP participants avow the fiction of their role-playing by, for example, wearing costumes or relegating their play to certain times.[31] In effect, Hoback the documentarian acts as a meta-baker, entering into the Q narrative in order to question the kind of activity it is and also producing Storm, a counternarrative that spotlights QAnon as a parasitic game within reality, upon which it feeds.

To be clear, Hoback does not suggest that all QAnon adherents are playing an ARG – their convictions, beliefs, and activities seem real. Rather, their reality is grounded in a game, as the final two episodes of Storm elaborate. In episode five, ‘Game Over’, Hoback calls QAnon the ‘descendent’ of an ‘Internet game’ titled Cicada 3301, itself speculated to be an ARG.[32] Hoback depicts the individuals who ran 8chan, and others who ran the anonymous web board 4chan (where Q-drops originated), as vying for control of the narrative of who is (or knows who is) Q. And in episode six, ‘The Storm’, after presenting Ron Watkins as Q, Hoback shows Ron’s father Jim marching to the US Capitol on January 6, proud of his son. ‘This wouldn’t be happening if… Q hadn’t been there, started as a LARP and became real.’ He says, ‘It’s American history now.’ Hoback threads the needle of playing and revealing the game carefully. He never denies that QAnon is real, but repeatedly affirms QAnon as grounded in a type of game that remediates the real world to produce an alternate narrative that shifts the ground of what truth in itself may be.

Because Hoback’s role in the ARG is that of an investigative documentarian, it is the investigative work described in the previous section that best reveals and conceals how he plays the game. What distinguishes Hoback-as-documentarian from Hoback-as-QAnon-participant is that his participation in the lives of Storm’s subjects exceeds documentation. He does not merely capture on film what they say and do, but materially affects their stories by being part of them. For instance, and most strikingly, Hoback makes himself an essential friend and confidant to key players: Across episodes four and five, he brokers a truce between the Watkins and their vocally critical ex-employee Fredrick Brennan, and helps Brennan flee the Philippines to the US when that truce breaks down. His moves in the social and technical dimensions of 8chan – the site through which Q-drops enter global social reality – transform QAnon’s wider story possibilities even prior to the docuseries’ release. For QAnon players (e.g. Anons, bakers, mods, admins), followers (e.g. Q-Tubers, citizens), and Storm viewers, Hoback’s influence is substantial enough to consider him a rival puppet-master jockeying for control of the Q narrative. Being ‘the filmmaker’ allows him to inch ever nearer to his subjects – not as a cat to a mouse, but as a player in a game of cat-and-mouse.

Hoback’s framing of Ron Watkins as Q in episode six demonstrates his skillfulness as both an investigative documentarian and an ARG player. In the climax of Storm, Hoback seemingly unmasks Watkins – but not by revealing evidence of the truth. Conversing after the November 2020 election, Hoback and Watkins vie over the possibility of knowing the truth. The conversation proceeds as if two old acquaintances are simply catching up. After all, Watkins had retired from administering 8kun (which replaced 8chan after it went offline following a series of livestreamed mass shootings). He recast himself publicly as a large-scale systems analyst and authority on voting machines. Subsequently, Watkins’ tweets about likely voter fraud had been retweeted in the thousands, including by President Trump, who was publicly sowing doubts about his election loss. When Hoback points out that Watkins has the ear of the president, insinuating a parallel with Q, Watkins deflects, reasserting simultaneously the terms of their relationship and of the game they’re playing:

Watkins: So, really curious to see if you figure out who Q is.

Hoback: Well, I don’t know if… I don’t know if there’ll be anything definitive.

W: Do you feel it’s a failure that you weren’t able to figure it out after so many years?

H: Um… I’m just kind of… chronicling all this…

W: Hm. But you’d want to have the smoking gun evidence.

H: You know, but I think that unless Q decides or comes out and says ‘Yes, I am Q,’ you know…

W: That’s never gonna happen, I think.

When it comes to Q’s identity, to ‘figure it out’ is always a truth-to-come and never a truth; many interviewees throughout the series agree that Q will never unmask. Watkins tells Hoback that he would want ‘a smoking gun’, Hoback’s ‘definitive’ proof, presumably metadata, digital fingerprints, or other evidence that ties a person to Q’s actions in a causal manner – things Hoback has spent episodes of Storm showing that Ron can conceal or fabricate. Hoback counters that, because those things are not forthcoming, figuring out who Q is is less about evidentiary truth and more about who has ‘motive’ to act as Q acts:

H: Right, so when you’re trying to figure out ‘Who is Q?’ you really have to look at motive. I mean, you have motive.

W: What’s my motive?

H: [Y]ou could’ve had motive to take down the mainstream media, to redpill the masses, you know, to get information out to people that wasn’t getting out any other way.

W: If you look at my Twitter feed, that’s what I’m doing publicly now.

Many people (from Anons to Q-followers to Q-Tubers to former President Trump) have motives to believe in – or otherwise entertain – Q’s provocations.[33] But figuring out who Q is, for Hoback, means determining whose behavior aligns with Q’s, who acts like Q even when they are not posing as Q or using Q’s tripcode, the unique digital signature that simultaneously marks users and keeps them anonymous. Watkins can literally post as Q by dint of being the administrator of the sole site to which Q is solidly tied. But Hoback instead points out that Watkins shares Q’s purported motives (i.e. critiquing the media, educating people, and disseminating information). When Watkins says that those activities are what he is doing now, his seeming defense – a rejoinder that sharing goals with Q does not make him Q – is a misstep. Hoback pounces on it:

H: It is what you’re doing publicly now.

W: I’ve spent the past, what, like almost three years every day doing this kind of research anonymously. Now I’m doing it publicly. That’s the only difference.

Watkins’ response to Hoback’s insinuation fails as a defense because, though he has not confessed to being Q, he has effectively confirmed that his public efforts on Twitter are similarly purposed. More than this, in aligning his ‘now’ with anonymous work he did for ‘three years’ on his board, saying that he has worked on Q’s agenda well before his current public forays, Watkins ‘slips up’, taking credit for the work one might attribute to Q as a puppet-master – creating clues, reading dig results, baking interpretations, and dropping more intel. The slip-up is not merely that Watkins contradicts his avowed neutrality in earlier episodes, it is that Watkins firmly aligns himself with Q’s motives.

Having cornered Watkins, Hoback interrupts the interview with an extended montage that doubles as a last episode series recap. Hoback showcases recorded instances of Watkins’ duplicity about knowing and not knowing about Q, and elaborates upon how the Watkins’ activities lent themselves to increasingly wider media and political circles, culminating in the QAnon phenomenon as a master conspiracy and ultimately provoking the January 6 insurrection. Importantly, the sequence does not unearth evidentiary truth. Rather, it is an argument, an interpretation of how divergent elements of the Q story, both real and fabricated, its actors, and their actions cohere as a plausibility – yet another truth-to-come. With Watkins now set up as Q, Storm returns to the same place in the conversation with Hoback:

W: Yeah, so, thinking back on it, like … it was basically three years of intelligence training, teaching normies how to do intelligence work. It’s basically what I was doing anonymously before, but never as Q. {Ron smiles, play stops}

H Voiceover: See that smile? Ron had slipped up. He knew it, and I knew it. And after three tireless years of cat and mouse, well … {play resumes, both laugh at length}

W: No, never as Q, I promise. Never as Q… ‘Cause I am not Q, {clears throat} I never was.

Hoback takes Watkins’ smile and nervous laughter as tells, presenting them as a confession.

Fig. 4: Ron Watkins and Cullen Hoback, ‘See that smile?’

He allows Watkins to protest too much, taking credit for anonymously teaching people to play Q’s game, ‘but never as Q’ – a line he repeats, and to which he adds ‘I am not Q and never was’ while clearing his throat. Though Watkins’ denial forecloses the possibility of a truth-to-come (i.e. an identity confession by Q), it nevertheless functions as a confirmation of the ‘curtain’ between Watkins’ public and private efforts and the veil concealing reality and alternate reality.

It is the move Watkins makes in speaking, not the meaning of his words, that matters. Because he has kept his behavior so secret – in fact, for years denying his participation in Q-research to Hoback – Watkins’ utterance does more than what it says. Effectively, Watkins has only stated, ‘I anonymously did /pol/ digwork on the board, just not as Q’, a mere clarification. After all, because 4chan, 8chan, and 8kun are all anonymous fora, it goes without saying that Watkins would be posting anonymously – every user is anonymous, not just Q. More than this, Watkins, as administrator of those boards, regularly posted with his admin handle, CodeMonkeyZ. Thus, he could simply be saying that he did intelligence work without his official handle. But the utterance’s semantics are less relevant than its performative dimension. While certainly a denial of any direct association between Watkins and Q, it is a denial misplayed.[34] In Hoback’s figuring, because Watkins has effectively avowed that his motives align strongly with Q’s, that denial transmutes into a confirmation that Watkins is (most likely) Q.

At this point in Storm, the series’ opening motivation – investigative truth – is practically irrelevant. What matters is truth-to-come and its force in shaping narratives that make reality what it is. The truth-to-come Hoback augurs is that the QAnon narrative is an alternate reality. In the absence of evidentiary proof, Hoback’s aim appears to show QAnon believers in their own language that the grounds of their convictions are a game: if you look closely, if you connect the dots, if you do the research, you will arrive at the plausible – nay, probable – conclusion that you are living within the confines of an ARG, and that Q is the puppet-master. Furthermore, that puppet-master is not a high-level government official, but Ron Watkins, a young, awkward, ethnically Othered nerd who lived much of his life across the Pacific. And Storm suggests to QAnon believers that Watkins has likely fooled them, siphoning their energies, anxieties, and personal capital to produce a coherent conspiratorial alternate reality, one that depends upon continued crowd-sourcing via contemporary media platforms – and done so effectively that, today, QAnon is arguably self-sustainable even without Q’s continued guidance. Insofar as Storm intervenes, it is not by undoing or unseating belief in Q, but by casting doubt upon him using the very sort of thinking and believing upon which he relies.

Conclusion

Storm is a noteworthy docuseries because it enters into the investigative spirit of its subject, the QAnon phenomenon. It seems to betray its own documentary inheritance in order to game, rather than destroy, the alternative reality underlying acts of disinformation that have contributed to white supremacist domestic terrorism. As we have shown, the two modes above are congruent rather than antithetical ways of productively interacting with rumors. Read in the investigative documedia mode, Storm teaches viewers to identify and follow clues, leading its viewers to a pre-standing ground of truth; read in the transmedia ARG mode, Storm also grooms viewers to identify and follow clues, but leads viewers to anticipate the next best thing, truths-to-come. Both modes necessitate reframing rumors and speculations as clues and possibilities. Watched with an eye and appreciation for Hoback’s skillfulness, we can learn much about the conspiratorial phenomenon that has appropriated and accelerated the rise of nationalistic, fascistic, and cynical tendencies in America and beyond,[35] especially how it came to be and how it sustains itself. But we do not learn to play the game as Hoback has, much less fully appreciate the ways games are serious. We may be left to despise it, perhaps feeling impotent to do anything about it. Such anxieties and worries are ultimately the same conditions that induce conspiratorial thinking in the first place.

In the end, Hoback’s docuseries struggles to inform audiences of a complex phenomenon in part because it attempts to intervene in it, doing so without reflecting upon the moves he is making. Hoback’s docuseries does not self-consciously reflect to the audience what he is doing, probably as he must disavow the QAnon game in order to play it. But without winking to his audience that his moves are moves, viewers are unlikely to see the usefulness of taking rumors seriously as a means to coming to grips with a vast, ever-shifting world. To live in a post-truth era means, seemingly, not to have a stable, univalent, or institutional account of what truth is. This is often taken to mean there is no truth. However, though accounts of truth are plural, their contradictions occlude but do not destroy truth. All investigations stand in for truth. As we see in Storm and the wider Q phenomenon, truth is enacted, mediated, and jockeyed over – in a word, performative. As Hoback’s docuseries demonstrates, that we draw our own truths is a condition of being human, neither novel nor hopeless. At its best, Storm teaches its audience how to enter into and play the game – but often fails at this, in part because to do so requires technical and media savvy as well as material and social capital that most people do not have.

But beyond this, when playing the game requires concealing that truths are constructed rather than found, and saying they are to-come rather than inherited, one cannot teach others how to think, only what to know or doubt and how to secure that knowledge or doubt. Considered in constellation with Stiegler’s concerns about the industrialisation of memory and the resulting loss of individuation, both the investigative documedia and the ARG logics at work in Storm likely leave viewers only with models of thinking that limit truth to a correspondence of some real to its representation, and truths-to-come to representable revelations. With only the residue of Hoback’s own performance, however, all we can see is the futility of his showing the game for what it is, rather than the im/potency of such games when you know (at last) how to play them.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Christopher McClintock and Professor Douglas Pastel for discussing Storm with us and for their helpful comments, as well as our anonymous reviewers.

Authors

Renée Pastel is Assistant Professor of Screen Studies in Boston College’s Communication Department. Her research concerns contemporary visual culture and the circulation of images across media forms, especially as media inform cultural memory. Her current manuscript project examines narrative figures across ‘War on Terror’ media, and how genre conventions mask the fracturing of national identity. Her work on the veteran figure’s reintegration recently appeared in Open Philosophy.

Michael Dalebout is a Lecturer in the Department of Rhetoric at UC Berkeley. Their research foregrounds the premise that technology shapes both social and psychic life to pursue an emancipatory vision of democratic participation. Their current book project analyses stand-up comedians’ digitally mediated acts of self-presentation, arguing that the political efficacy of comic voices in the age of the online digital public sphere is about ‘standing up’. Their article on Wittgenstein, media, and humor recently appeared in Jeunesse: Young People, Texts, Cultures.

References

Adleman, D. ‘“Where We Go One, We Go All”: QAnon and the Mediology of Witnessing’, Crisis and Communication, Vol. 8, No. 1, 2021: 1-27.

Austin, J. How to do things with words. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1961.

Berkowitz, R. ‘QAnon resembles the games I design’, Washington Post, 11 May 2021: https://www.washingtonpost.com/outlook/qanon-game-plays-believers/2021/05/10/31d8ea46-928b-11eb-a74e-1f4cf89fd948_story.html

Bloom, M. and Moskalenko, S. Pastels and pedophiles: Inside the mind of QAnon. Stanford: Redwood Press, 2021.

Braun, J. and Eklund, J. ‘Fake News, Real Money: Ad Tech Platforms, Profit-Driven Hoaxes, and the Business of Journalism’, Digital Journalism, Vol. 7, No. 1, 2019: 1-21.

Bruzzi, S. New documentary, second edition. New York: Routledge, 2006.

_____. ‘The Performing Film-maker and the Acting Subject’ in The documentary film book, edited by B. Winston. London: BFI/Palgrave Macmillan, 2013: 48-58.

Chang, A. Playing nature: Ecology in video games. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2019.

Clements, J. ‘Environmental Impact: Media Ecology and QAnon’, Master’s Thesis, Valdosta, GA: Valdosta State University, 2021.

DiFonzo, N. ‘Conspiracy Rumor Psychology’ in Conspiracy theories and the people who believe them, edited by J. Uscinski. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2018: 257-268.

Edy, J. and Risley-Baird, E. ‘Rumor Communities: The Social Dimensions of Internet Political Misperceptions’, Social Science Quarterly, Vol. 97, No. 3, September 2016: 588-602.

Eitzen, D. ‘The Duties of Documentary in a Post-Truth Society’ in Cognitive theory and documentary film, edited by C. Brylla and M. Kramer. New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2018: 93-111.

Fallon, K. Where the truth lies: Digital culture and documentary media after 9/11. Berkeley: University of California Press, 2019.

Gilbert, S. ‘The New QAnon Docuseries Is a Gamified Mess’, The Atlantic, 21 March 2021: https://www.theatlantic.com/culture/archive/2021/03/hbos-q-into-the-storm-is-a-gamified-mess/618342/

Haiven, M., Kingsmith, A., and Komporozos-Athanasiou, A. ‘Whither Harmony Square?: Conspiracy Games in Late Capitalism’, The Los Angeles Review of Books, 13 November 2021: https://lareviewofbooks.org/article/whither-harmony-square-conspiracy-games-in-late-capitalism/

Harindranath, R. ‘Veridicality and the truth claims of the documentary in the post-truth era: Rethinking audiences’ ‘horizon of expectations’, Participations, Vol. 15, No. 1, May 2018: 398-411.

Hunter, M. and Hanson, N. ‘What is investigative journalism?’ in Story-based Inquiry. UNESCO, 2011.

Jobs, S. ‘The Importance of Being Uncertain – or What I Learned From Writing History with Rumors’, European Journal of American Studies, Vol. 15, No. 4, 2020: 1-16.

Kristiansen, E. ‘Alternate Reality Games’ in Situated design methods, edited by K. Friedman and E. Stolterman. Cambridge: MIT University Press, 2014: 241-257.

Nichols, B. Representing reality: Issues and concepts in documentary. Indianapolis: Indiana University Press, 1991.

Roberts, B. ‘Cinema as mnemotechnics: Bernard Stiegler and the “industrialization of memory”’, Angelaki, Vol. 2, No. 1, 2006: 55-63.

Sardarizadeh, S. Twitter Post. 5 Apr 2021, 1:21 AM: https://twitter.com/Shayan86/status/1378940826311663620

Sesmondo, S. ‘Post-truth?’, Social Studies of Science, Vol. 47, No.1, 2017: 3-6.

Steyerl, H. ‘Documentary uncertainty’, Re-visiones, 2011: http://re-visiones.net/anteriores/spip.php%3Farticle37.html

Stiegler, B. ‘DOING AND SAYING STUPID THINGS IN THE TWENTIETH CENTURY: bêtise and animality in deleuze and derrida’, Angelaki, Vol.18, No. 1, 2013: 159-174.

_____. Technics and time 3: Cinematic time and the questions of malaise. Stanford: Stanford University Press, 2011.

Thompson, C. ‘QAnon Is Like a Game – a Most Dangerous Game’, Wired, 22 September 2020: https://www.wired.com/story/qanon-most-dangerous-multiplatform-game/

Williams, L. ‘Mirrors without Memories: Truth, History, and the New Documentary’, Film Quarterly, Vol. 46, No. 3, Spring 1993: 9-21.

Wynants, N (ed.). When fact is fiction: Documentary art in the post-truth era. Amsterdam: Valiz, 2019.

Zuckerman, E. ‘QAnon and the Emergence of the Unreal’, Journal of Design and Science, Vol. 6, 2019: https://jods.mitpress.mit.edu/pub/tliexqdu/release/4

[1] See Sardarizadeh 2021: https://twitter.com/Shayan86/status/1378940826311663620

[2] Bloom & Moskalenko 2021, p. 21.

[3] See Eitzen 2018, Williams 1993, and Steyerl 2011 for further discussion of what documentary truth ‘is’.

[4] See Sesmondo 2017, pp. 3-6; Wynants 2019; Harindranath 2018, pp. 398-411.

[5] See Jobs 2020, p. 6.

[6] Edy & Risley-Baird 2016, p. 590.

[7] See Edy & Risley-Baird 2016; DiFonzo 2018.

[8] DiFonzo 2018, p. 258.

[9] QAnon is a mega-conspiracy that enfolded pre-existing conspiracies, including #Pizzagate. See Adleman 2021.

[10] Bruzzi 2013, p. 49. Although Storm could be fruitfully examined as a performative documentary, this line of inquiry would lead too far astray from our current project.

[11] Stiegler 2006, p. 59.

[12] Stiegler 2011, p. 77.

[13] Roberts 2006, p. 60.

[14] Ibid.

[15] Stiegler 2013, p. 170.

[16] An inversion of Bruzzi’s ‘author-performer’, Bruzzi 2013.

[17] Hunter & Hanson 2011, p. 8.

[18] Ibid.

[19] Eitzen 2018, pp. 93-111.

[20] Ibid., p. 104.

[21] Nichols 1991, pp 3-6.

[22] Ibid., p. 123.

[23] Fallon 2019, p. 166.

[24] Gilbert 2021.

[25] Bruzzi 2006, p. 214.

[26] Chang 2019, p. 51.

[27] Zuckerman 2019; Thompson 2020.

[28] Clements 2021, p. 5.

[29] Chang 2019, p. 50.

[30] In episode one, Hoback represents Jack Posobiec as first to call Q a LARP, after Posobiec went to Comet Pizza and failed to verify the #Pizzagate pedophilia conspiracy. Subsequently, QAnon adherents rejected Posobiec for not taking the conspiracy seriously.

[31] For connections between QAnon and LARP, see Bloom & Moskalenko, Pastels and Pedophiles, pp. 7-10.

[32] Kristiansen 2014; Haiven & Kingsmith & Komporozos-Athanasiou 2021; Berkowitz 2021.

[33] See Braun & Eklund 2019.

[34] In speech act theory, performatives are utterances that do rather than describe something (e.g. ‘I promise’ makes a promise, it does not report on one). There are many ways performatives can go wrong. One way is to ‘misplay’ a performative, using a valid performative convention but in circumstances in which (or as a person for whom) it fails, doing something else. For Watkins, to say ‘I am not Q’ while at once avowing and concealing so much in common with Q is a performative denial that, in failing, inverts itself (not merely a true/false statement). Austin 1961, p. 18; 34.

[35] On QAnon’s global spread, see Bloom & Moskalenko 2021, pp. 149-174.