Selling film in the summer of 2015: Midnight Sun, Il Cinema Ritrovato, and Karlovy Vary

In the summer of 2015 I undertook an eight-week journey from Istanbul to Paris (part of a year-long research project documented on my blog The Itinerant Cinephile[1]) that involved visits to film festivals, independent theaters, and exhibition venues throughout the United States and Europe. With the practice of public movie-going imperiled as never before, I wanted to document those places and proprietors that continue to make it possible for audiences to see films theatrically and communally, particularly those that regularly screen films outside of the commercial mainstream, that celebrate film’s illustrious history with retrospective series, that cater to a local audience, and that do so without sizable financial backing. In so doing, I aimed to address that most urgent question within film studies and the film industry: how should ‘old’ and ‘new’ media co-exist to preserve the legacy of film while embracing new technologies and a radically altered media landscape? The trip was funded by the Mary Elvira Stevens Traveling Fellowship, awarded to Wellesley College alumna in pursuit of ‘purposeful travel into unfamiliar territory that will inspire reflection and growth and lead to more fulfilling and productive personal and professional lives’.[2]

My interest in traveling to Europe stemmed from its proximate yet distinct relation to the United States film market, knowing that European governments had institutionalised support systems for film through subsidies and incentives, bolstered by an ideologically healthier if still financially-strapped climate of cultural organisations promoting Europe’s cinematic arts domestically and abroad. The degree to which this model is translatable to the United States market (where state and city governments are experimenting with incentives for local production and exhibition) was a key question motivating my interest. I hoped to gain a fresh perspective on exhibition practices and customs while extending my understanding of the challenges for small theaters contending with Hollywood’s market dominance and global media conglomeration. Recognising at the outset that independent cinemas are a dying breed on both sides of the Atlantic, I knew film festivals would feature importantly in my reconnaissance. From the intrepid research and illuminating insights to have emerged from the burgeoning field of film festival studies, I understood that notions of European festivals remaining untainted by commercialism were naïve; degrees of artistic compromise and devaluing of filmmaker interests have pervaded even the most experimental and exacting of festivals, as Marijke de Valck documents in her study of the International Film Festival Rotterdam.[3] The three I opted to attend offered up a nicely-diverging range for comparison of the key elements through which I wished to assess the fortitude and sustainability of their business models and creative missions: sales (the logistics of festival ticketing); exhibition (the venues for and modes of screening films); and programming (the films selected for screening).

Though it can be overshadowed by the glitz and fanfare, the foremost objective of film festivals is to sell films. In the most literal sense this means selling distribution rights as well as festival tickets. As festivals sprout like mushrooms worldwide and the chronic foundering of independent cinemas compels films to spend more time touring on the festival circuit, such films often arrive at a festival with domestic and/or foreign distribution deals already sealed. In those cases the festival functions to sell the film down the road by upping its profile through potential awards, critical opinion, and social media attention. Increasingly, then, the selling of films at festivals is figurative rather than literal.

Digital restoration is exploding as yet another marketing scheme for selling ‘film’. This year’s major re-releases – Satyajit Ray’s Apu trilogy (Pather Panchali [1955], Aparajito [1956], and The World of Apu [1959]), The Long Good Friday (John Mackenzie, 1980), The Third Man (Carol Reed, 1949) – were omnipresent on the summer 2015 festival circuit across Europe and in the independent theaters along the route. As it seems that just about every conceivable city, town, municipality, and region now boasts a film festival, these events have come to serve as a centerpiece of the local tourist trade as well as an indispensable opportunity to codify a national or regional cinema identity;[4] it is the scenic location and civic spirit, alongside the films themselves, that festival-goers are sold on. Moreover, with individual festivals increasingly needing to stand out from the proliferating clutter, they must shape a distinct brand for themselves – something that the three festivals discussed below each endeavored to do in their 2015 editions, working respective modes of literally selling themselves by figuratively ‘selling film’.

Selling film-going: Midnight Sun Film Festival

Celebrating its 30th year, Midnight Sun[5] ran from June 10 to 14 in the remote Lapland town of Sodankylä, Finland, nearly 1,000 kilometers north of Helsinki. Co-founded by Finnish filmmaking brothers Aki and Mika Kaurismäki, the festival was long shepherded by the tireless Finnish-born critic-historian-filmmaker Peter von Bagh, whose passing last September was resoundingly commemorated in this year’s programming. Midnight Sun has more than mastered the art of self-branding, managing to lure enough cinephiles 120 kilometers north of the Arctic Circle to sell a reported 30,000 tickets this year. Their primary means of seduction is time and place: the titular unrelenting light bathing a wilderness of glassy lakes and grazing reindeer makes for a singular if disorienting timetable and landscape. The awaiting reality is part summer camp, part tourist trap – charming in its ragtag do-it-yourself-ness yet tacky with trumped-up attractions and inflated costs, even as Sodankylä and environs are severely underserved for lodging, restaurants, public bathrooms, Internet service, and other basic amenities.

Seeming to intuit that those enticed to this almost eerily silent outpost might revolt if left unstimulated for long, Midnight Sun’s programming continues around-the-clock, starting with morning discussions with special guests broadcast live on Finnish television and staving off sleep with screenings of the festival’s edgier fare in the wee hours. Just as Jean-Luc Godard said that cinema was invented with the projector, thereby ontologically privileging the projection of images over their recording, so does Midnight Sun bill the communal screening experience as paramount. Not a festival at which film sales are prominent, forthcoming releases constitute only half of the program. The emphasis instead is on spectatorship, in both its immersive and interactive varieties, with this year’s audiences treated to 70mm prints of 2001: A Space Odyssey (Stanley Kubrick, 1968) and Vertigo (Alfred Hitchcock, 1958), a chilling midnight screening of Under the Skin (Jonathan Glazer, 2013), silent films with live musical accompaniment led by conductor-pianist Antonio Coppola, and karaoke sing-alongs to musical films, including my best-of-fest – the narratively-impaired but irresistible Prince vehicle Purple Rain (Albert Magnoli, 1984).

The problem lies in the fact that, for a festival that privileges the spectatorial experience, Midnight Sun is not up to the job, theatrically speaking. However atmospheric, the 1,000-seat Big Tent and its smaller sidekick are under-heated, overly bright (plastic flaps no match for the midnight sun), and cursed with rear-numbing folding-chair seating and sightlines often obstructed by tent poles. Cinema Lapinsuu, billed as the ‘festival palace’, is hardly palatial; the additional indoor venue Koulu (School) lacks an egress, turning it into a veritable fire trap and making me concerned for the well-being of Sodankylän schoolchildren. Crowd management there and elsewhere was non-existent and there were faults with the projection at nearly every screening I attended. I had not anticipated that the website[6] proclamation that ‘von Bagh valued the sense of community brought on by the cinema-experience even more highly than the correct screening format’ would be manifested quite so literally.

Fig. 1: Queuing for a screening in the Big Tent at the Midnight Sun Film Festival.

Knowing that another key draw to the festival experience is having filmmakers in attendance, Midnight Sun summons prestige guests to these hinterlands and schedules them for the morning discussions and master classes. Regrettably, these VIPs seem infrequently on hand for their film showings themselves – and when they do put in appearances it is impromptu rather than announced on the program. Apart from Christian Petzold’s charming but brief introduction of his arresting first feature The State I Am In (2000), none of this year’s guests (including Mike Leigh, Nils Malmros, Miguel Gomes, and Whit Stillman) graced screenings I attended. While the printed schedule was short on details it was long on revisions and confusing notations; a new schedule was circulated daily, in alternating colors, and looking like it had been mimeographed in the 1970s. Failing to read the fine print resulted in my late discovery that Petzold’s German-language film Barbara (2012) was screening with Swedish and Russian subtitles. Though Midnight Sun possesses an unmistakable magic, ultimately I felt hoodwinked by what was undoubtedly a masterful marketing scheme that enticed me into traveling far off the beaten path at considerable expense.

Selling film as history: Il Cinema Ritrovato

Now in its 29th year, Il Cinema Ritrovato[7] took place in Bologna, Italy from 27 June to 4 July. Its mission to promote the restoration and preservation of film continues throughout the year through the efforts of the festival’s primary sponsor, the Fondazione Cineteca di Bologna. Like its unofficial sister festival (and competitor) in Pordenone, which screens silent film exclusively, Il Cinema Ritrovato promotes film’s past and future by selling film in the literal sense – as the photographic stock derived from an emulsified base (such as celluloid) used to imprint visual images that, having undergone chemical processing, are projected onto screens using optical-mechanical elements. 35mm prints still constitute more than half of the program at Il Cinema Ritrovato, and the emphasis on historical accuracy extends to all films being shown in their original language, with Italian and English subtitles added (a rare treat in Italy).

Von Bagh’s ghost also lingered here, where he was artistic director since 2001, and his programming legacy remains staunchly committed to the festival’s ‘recovered and rediscovered’ mission. Highlights of the program’s four sections (Cinephiles’ Heaven, The Time Machine, The Space Machine, and a special sidebar for children and young people) included the following: short films restored as part of the ongoing Charlie Chaplin and Buster Keaton Projects, dedicated to salvaging the complete works of the silent era comedians; a rarely screened 3D print of The Wizard of Oz (Victor Fleming, 1939); the World Cinema Project restoration of Ousmane Sembène’s La Noire de…(1966); the first of a two-part series devoted to Soviet filmmaking from the early years of the Thaw; the complete version of Louis Feuillade’s serial Les Vampires (1915-16) serial, doing double duty in representing the series 120 Years of Gaumont and A Hundred Years Ago; the series Jazz Goes to the Movies, co-curated by Ehsan Khoshbakht and Jonathan Rosenbaum; the long-awaited restoration of Chantal Akerman’s landmark Jeanne Dielman…(1975), realised through the tenacious efforts of restorers at the Belgian Cinematek; and a series of 1950s Japanese studio films highlighting that nation’s transition to color photographic processes. Of course, privileging history over quality means that some duds will be unavoidable. For me these were the stagey Julien Duvivier melodrama La Fin du Jour (1939), the preachy Bergman-Rossellini collaboration Europa ’51 (1952), and the unengaging documentary Visit or Memories and Confessions (2015), which I understand why director Manoel de Oliveira refused to release until after his death.

As critically important as the archive is, it is hardly one whose practices are easily translatable to lay persons. Inevitably, there were some long-winded, overly technical introductions to sit through. It is testament to the structure of the proceedings and its participants then that the Future of Film panel, despite taking place over two stifling hours in a standing room-only auditorium, was thoroughly engrossing.[8] The lively, informative discussion was moderated by Variety critic-turned-Amazon executive Scott Foundas and featured an alternating array of illustrious filmmakers and archivists – though only one woman (FIAF’s Rachael Stoltje). For all their despairing about the current state of emergency regarding the processing, projecting, and preserving of film prints, the panelists were rousing in their impassioned calls to arms and for collaboration. Director Alexander Payne proclaimed that he cares not that movies are shot on film, only that they are projected on film – ‘flicker will always be superior to glow’. Sony’s Grover Crisp offered a saucy rejoinder in response, singling out Bologna’s own Cinema Arlecchino as hardly exempt from the deterioration of film projection caused by poorly trained projectionists using badly-maintained equipment. The most resounding note was sounded by Josè Manuel Costa of the Cinemateca Portuguesa in speaking of archives as museums of film history, with his reminder that art history is not viewed in terms of the perfect image. Thus, the imperfections that result from film’s technological base are an indelible part of the art form.

Fig. 2: Future of Film panel at Il Cinema Ritrovato, featuring (left to right) Scott Foundas (Amazon), Nicola Mazzanti (Cinematek Belgium), and filmmakers Pietro Marcello and Alexander Payne.

After the frustrations of Midnight Sun, Il Cinema Ritrovato seemed infinitely simple in its first-come, first-serve approach to ticket-buying, and even with a non-VIP pass I got into every screening I attempted. The only downside was waiting in crowded, non-air-conditioned theatre lobbies for the previous screenings to let out – Bologna in early July was as sweltering as Lapland in early June was chilling. Purple Rain singalong aside, ultimately I was most swayed by the spectacular draw of communal film-viewing not in Lapland but in Bologna, where the evening screenings in the Piazza Maggiore offered proof of what esteemed guest Isabella Rossellini, there to introduce Casablanca (Michael Curtiz, 1942) as part of a retrospective of her mother Ingrid Bergman’s pre-Hollywood films, called ‘il festival più bello del mondo’. With around 5,000 people filling the square nightly with a sea of bodies sprawled on every surface, the assembled crowd remained respectfully hushed in a way that al fresco film audiences rarely are in my experience. However, an eruption came on the final night, with an immense swell of applause after the chill-inducing opening credits of 2001: A Space Odyssey, scored to the unforgettable strains of Strauss’ Also Sprach Zarathustra. It was an electrifying start to the screening of what remains an awe-inspiring film and a rousing reminder of how much communal spectatorship matters. For all the exhortations (some hollow, some sound) to embrace digital production processes and distribution/exhibition practices, I was reminded how new technologies threaten our common language of cinema and our shared experience of its public exhibition.

Selling the business of film: Karlovy Vary International Film Festival

Billing itself as one of the oldest A-list festivals (i.e., FIAPF-sanctioned non-specialised festivals with a competition for feature-length fiction films), now in its 50th year, KVIFF[9] is the predominant festival in Central and Eastern Europe, with around 200 films showcased and a reported 11,000 attendees. It clearly operates according to what Mark Peranson calls the ‘business model’ of film festivals, as opposed to the ‘audience model’ that Midnight Sun and Il Cinema Ritrovato employ.[10] Much changed since its socialist-era function as a tool of the Soviet propaganda machine, KVIFF was taken over in the early 1990s by Czech actor Jiří Bartoška and film journalist Eva Zaoralová. In its contemporary incarnation it strives to be thought of as Cannes-in-Bohemia. The spa town that houses it features some grand old-world hotels including the Bristol Palace, supposedly the inspiration for The Grand Budapest Hotel (Wes Anderson, 2014), though I would presume some Hungarian hotelier might dispute that. These along with the surrounding green hills and cool breezes made for an enticing enough setting, even if the local custom of ‘taking the waters’ seems a fairly ludicrous scam on which to build a tourist destination. What I imagine is typically a quaint town is transformed during the festival into what I would describe as Euro Spring Break: a mecca for summer-loving Czechs, seemingly there for reasons beyond cinephilia, to which the electronic dance music blaring from the Finlandia pop-up bar in the middle of the night is testament.

Befitting a corporate-scaled festival, the overcomplicated ticketing system at Karlovy Vary favored these day-trippers and late-comers in ways that seemed dismissive of more committed cinephiles who were thereby forced to contend on a daily basis with the chaos at festival headquarters in the Thermal Hotel, which featured nineteen individual ticket desks, each of which seemed equipped to handle only a single task. Feeling nostalgic for what now seemed the charmingly disorganised Midnight Sun, let alone the easy and equitable Il Cinema Ritrovato, I continued to find KVIFF alienating in ways that other large-scale festivals I have attended (Sundance, Edinburgh, Sydney) do not. Though less focused on communal exhibition than Midnight Sun, here too the problem of unfit screening spaces persisted. Of the fourteen festival venues only the Thermal’s Grand Hall and the Čas Cinema are up to theatrical standards, with the majority of ‘cinemas’ being merely retrofitted hotel banquet ballrooms.

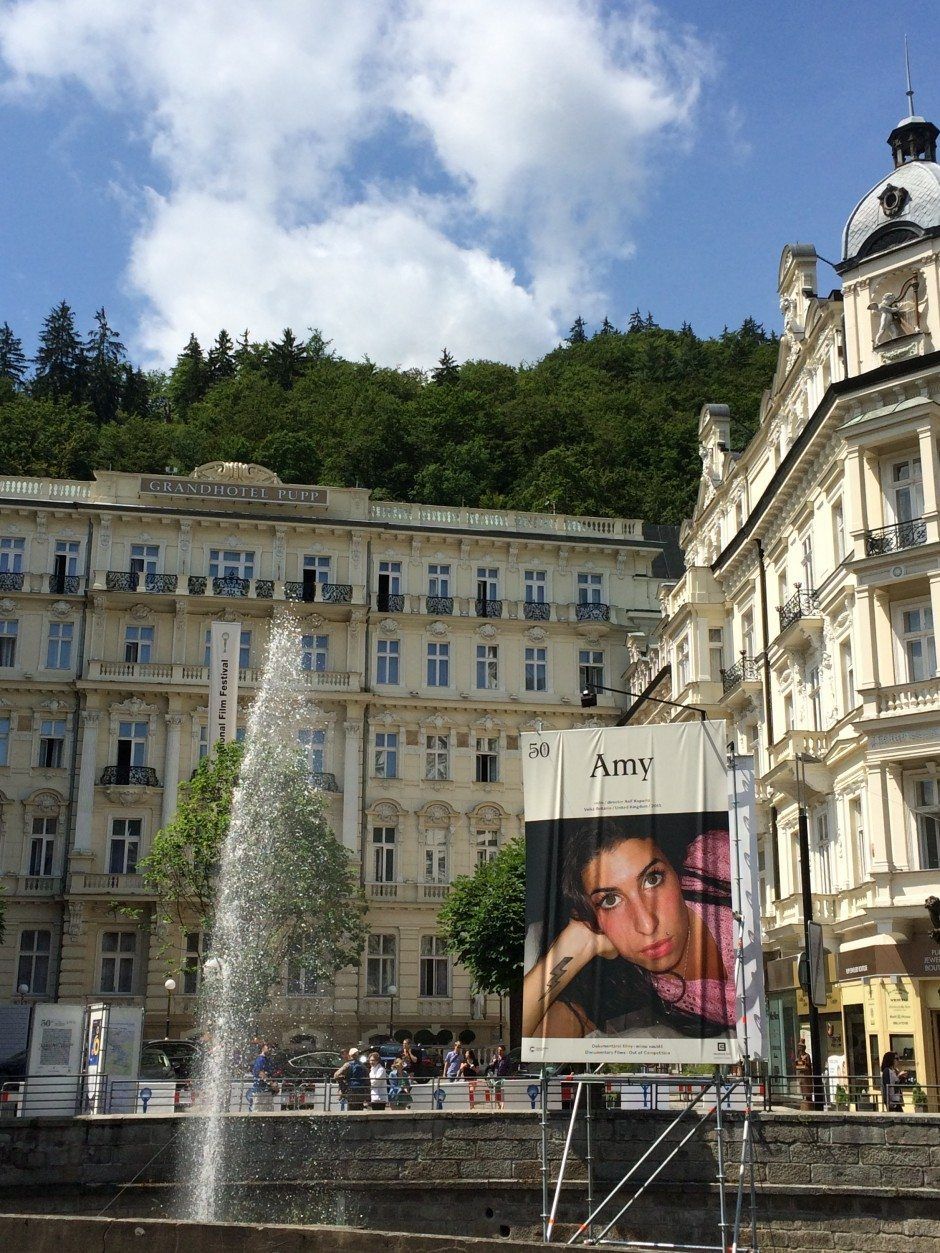

Fig. 3: The Grandhotel Pupp, one of the screening venues at the Karlovy Vary Film Festival.

For all its touting of regional cinemas – an East of the West section is devoted to screening debuts and second feature-length films from Central and Eastern Europe, the Balkans, Greece, Turkey, and the countries of the former Soviet Union – KVIFF displays an infatuation with Hollywood that is odd for a European festival. The Crystal Globe for Outstanding Artistic Contribution to World Cinema, bestowed annually, has been awarded predominantly to white men working in Hollywood. This year’s recipient Richard Gere is a prime example of the dubious selection process. The adoration continued with much-hyped appearances by Harvey Keitel, Udo Kier, and George Romero, though here again it was too infrequently the case that filmmakers were in attendance for Q&As, just as there was an ostensible lack of cinephile presence discernable throughout the festival. At the expense of attending cinephiles, then, KVIFF seems squarely focused on the business of film: Hollywood-touting; tourist destination-forging; and to more artistically productive ends, the Works in Progress platform, providing career-nurturing outreach to young filmmakers who bring uncompleted projects to the festival for unofficial premieres aimed at landing finishing funds, co-production partners, and sales agents.

The business of film (or of film festivals) seems to have afflicted the programmed films with a condition I would name festival-itis, which was by no means endemic to KVIFF. Seemingly the result of attempting to stand out from the considerable crowd of films vying for attention, filmmakers try to do too much, and fall short in the process. Symptoms I noticed across festivals include: the obtrusive hybridising of genres and erratic changes of tone (Yi’nan Diao’s Black Coal, Thin Ice [2014]; Lisandro Alonso’s Jauja [2014]; Bruno Dumont’s Lil Quin’quin [2014]); overly emphatic atmosphere and ponderous performances (Jörn Donner’s excessively reflexive biopic Armi Alive! [2015]; the Schwarzenegger-starring ‘alt-zombie’ indie Maggie [Henry Hobson, 2015]), British sex traffic melodrama The Incident [Jane Linfoot, 2015]); and the epic-scaled yet emotionally empty or overreaching (Mia Hansen-Løve’s Eden [2014]; Yorgos Lanthimos’ The Lobster [2015]; Jia Zhangke’s Mountains May Depart [2015]). The best new films I saw at KVIFF were ones that scaled small, stayed consistent in tone and genre, and though emotionally-muted still spoke volumes: Adrián Biniez’s El Cinco (2014); Lucie Borleteau’s Fidelio, Alice’s Odyssey (2014); Micah Magee’s Petting Zoo (2015); Ognjen Svilicic’s These Are the Rules (2014); and Paz Fabrega’s Viaje (2015). These were the works – personal, observational, modest, and moving – that seemed ultimately the most adept at selling the art of film.

For all the consistencies both welcome (von Bagh’s imprimatur, The Third Man restoration showing up around every bend) and discouraging (the festival-itis diagnosed above), there is no doubt that these festivals, alongside the art house cinemas and alternative exhibition venues I visited along my way, provide a blessed respite from the soulless spaces of corporate cinema chains and the stultifying fare they screen. The most dismaying consistency I noted in my travels across Europe was the degree to which commercial cinemas were playing the same studio films showing back home – Hollywood globalisation manifested as a perverting of the ‘now playing at a theatre near you’ pledge. In the face of such American-centric cinematic homogeneity, Julian Stringer notes that film festivals have come to play a key, if often underacknowledged, role in the writing of film history. Festival screenings determine which movies are distributed in distinct cultural arenas, and hence which movie critics and academics are likely to gain access to.[11]

Of course the politics of programming film festivals are exclusionary in their own right and hardly immune from commercial concerns with their auteur-adoration and aforementioned overlooking of the modest for the flashy. Still, in this late cinematic moment with, as critic Manohla Dargis alleges, ‘too many lackluster, forgettable and just plain bad movies’ coursing through ever more abundant if audience-alienating distribution channels, far surpassing the requisite number of eyeballs, festivals are the first stop for the ‘curation over consumption’ that Dargis advocates.[12] Whether subscribing to the business model or the audience model (or some hybrid of both), those festivals that are committed to selecting truly innovative work and to screening it in ways that allow cinephiles both to commune and communicate with each other and with audiences down the distribution chain will serve as cinema’s ambassadors for selling film in the much-transformed landscape of its second century.

Maria San Filippo (University of the Arts in Philadelphia)

References

Dargis, M. ‘As Indies Explode, An Appeal for Sanity’, New York Times, 9 January 2014: http://nyti.ms/1bUFbbH (accessed on 3 October 2015).

De Valck, M. ‘Supporting art cinema at a time of commercialization: Principles and practices, the case of the International Film Festival Rotterdam’, Poetics, Vol. 42, 2014: 40-59.

Peranson, M. ‘First You Get the Power, Then You Get the Money: Two Models of Film Festivals’ in Dekalog 3: On film festivals, edited by R. Porton. London: Wallflower, 2009: 23-37.

Stringer, J. ‘Global Cities and the International Film Festival Economy’ in Cinema and the city: Film and urban societies in a global context, edited by M. Shiel and T. Fitzmaurice. Malden: Blackwell, 2001: 134-143.

[1] http://www.itinerantcinephile.com

[2] http://www.wellesley.edu/cws/fellowships/wellesley

[3] See de Valck 2014.

[4] For a discussion of the significance of film festivals in shaping civic and geographic spheres of cultural production and identity see Stringer 2001.

[5] http://www.msfilmfestival.fi/index.php/en/

[6] Ibid.

[7] http://festival.ilcinemaritrovato.it/en/

[8] The Future of Film panel is viewable in its entirety on the Cineteca di Bologna YouTube site: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=J427vQTxvbc&feature=youtu.be (accessed on 20 August 2015).

[9] http://www.kviff.com/en/homepage

[10] See Peranson 2009.

[11] Stringer 2001, p. 134.

[12] Dargis 2014.