Documenta Fifteen and Berlin Biennale 12: A comparative review

The thematic contents of the Berlin Biennale 12 and documenta 15, which both took place in Summer 2022, are certainly close, ‘focusing on themes of colonialism and decolonization … art as an opportunity to repair’[1] even though ‘documenta fifteen is practice and not theme based’,[2] its themes also follow decolonisation and demonstrating the continued presence of (neo)colonisation. Indignation and a need to heal animate both events. Kader Attia writes about wounds created by narcissistic and self-destructive Western belief in its own superiority based on the Promethean myth of modernity, science produced knowledge combined with overproducing capitalism hegemonising over other worldviews and nature[3] that require reparation with art as the only power able to oppose imperialism’s seeds of fascism.[4] The ruangrupa collective, which was invited to curate documenta, states directly and simply: ‘We refuse to be exploited by European institutional agendas that are not ours to begin with.’[5]

Despite content similarities or superficially similar choices of artists (both events invited a lot of underrepresented artists from the Global South), the biennale curated by Attia has not been under any such scrutiny from the German public as has ruangrupa’s exhibition. Attia has taken a conventional approach in his meticulous and slightly academic curation – thus more amicable, whereas ruangrupa has opted for an almost frontal attack, a revolution to the established format (although seen before) and a takeover, occupy-style, of the established institution for 100 days. As ruangrupa’s September 10th letter well shows,[6] this revolution has a price to pay. The calls to either remove certain pieces or shut down the whole event, due to perceived anti-Semitism, appeared before the opening of the exhibition (starting with an anonymous blog entry in January picked up eventually by the Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung – FAZ). I would like to propose that a significant difference between these two events lies in the style of curation.

Situating the exhibitions

documenta (always written without the first capital letter except for Documenta 11) has almost 70 years of history. Established to bring avant-garde art back to Germany after it had been banned by the Nazis, it has become a mega-event, happening every five years, a tourist attraction that brings almost a million visitors to the northern Hessen town Kassel.[7]documenta often also brings controversy: a blow to the institutional history of the initiative was the revelation that art historian Werner Haftmann, documenta co-founder and the co-director of the first three editions, was an anti-Semite, a former Nazi, and a war criminal.[8]

documenta fifteen (www.documenta.de; https://linktr.ee/documentafifteen) and its director Sabine Schormann (resigned as of 17 July 2022) invited ruangrupa in 2019, an artist collective from Indonesia, to curate the event. The collective started right away with introducing their ‘lumbung’ practice as the core way of working on curation and art. Their reaction to the invitation was the following:

instead of integrating ourselves into the long-established documenta system, we decided to stay on our path. We invited documenta back, asking it to be part of our journey.[9]

The working collective was established in 2000 post-dictatorship Jakarta[10] and represents a new way of making art, embedded in Indonesian modern art history. Their method, lumbung, is connected to what Elly Kent calls ‘conscious collectivity’ that is part of a longer cultural history in Indonesia,[11] and it consists of ‘community as art’ as a method of work.[12] In a way, ruangrupa put in practice what other documentas and biennales have been accused of only performing: democracy and egalitarianism.[13]

The Berlin Biennale for Contemporary Art was established to cater to the younger generation of contemporary artists and their public alike, with a comparatively short history that might not feel as established as documenta’s. It was founded in 1998 by Klaus Biesenbach, director of the KW Institute for Contemporary Art, its main venue in symbolic and organisational terms. The description of the biennale’s goals and values by the BB foundation points to its glocality, focusing on trends and cultural issues that make it experimental and innovative in a sense of an ‘art lab’.[14] Years later, while openness and inclusivity, as well as more learned self-awareness have prevailed, the fun seemed to have been set aside. Despite the foundation’s claim that it follows the trend of biennialisation as a way to promote the city, the Berlin Biennale 12 proves itself as more than that.

documenta fifteen method

This was the first time documenta has been curated by a collective, and by person/s from Asia.[15] In the past individual artists from the Global South (mostly East Asia, South Asia, the Middle East, and Africa) were not exhibited in such big numbers. This is the first such large exhibition of Global South artists in Europe, with about 1,500 artists involved. The focus of ruangrupa has not been ‘beauty’, shock value, novelty, technology, contemporaneity, or any of the other values that might be associated with art biennales. Instead, their focus has been on solidarity, sustainability, decolonisation, the collective – all repeatedly mentioned, presented, and enacted in various forms of lumbung in Kassel. The ruangrupa collective said that commentators suspected that there would be ‘an exhibition of non-art’,[16] suggesting that the exhibitions and art require a redefinition.

The curators’ proud answer was: ‘We are not in documenta fifteen, we are in lumbung one.’[17] The show became part of a continued practice of lumbung, well summed up by ruangrupa’s recommendation for their invited artists: ‘keep doing what you’re doing … and find a translation to Kassel’.[18]

Lumbung is rooted in village life; it refers to a rice barn storage for villagers’ harvests that is managed collectively.[19]The experience of it was like stumbling upon a bustling village of artists, practicing art, dealing in ‘experimentation and playfulness’.[20] Instead of the initial centralised format of ‘harvesting’, ruangrupa developed the concept of a system where a collective of collectives propagated rhizomatically and indefinitely.[21] There is a strong focus on economics and sustainability for lumbung artists, threaded throughout all of their writing and actions. With the call to ‘decentralize the center’[22] ruangrupa employed a DAO (Decentralised Autonomous Organisation) as part of ‘experimentation on currencies’ and organisation. The sales happening behind the scenes in previous documentas changed to selling art pieces upfront, with profits distributed evenly among the artists. This is an active practice proposed as a solution to an exclusive Western gallerist and art market economy. However, I do not find that this decentralised/anarchist system of working is effective in dealing with the accusations documenta/lumbung faced. The use of a DAO or the collective of collectives methods, where the exhibition authority is ‘subcontracted many levels away from the main curators’,[23] responsibility and accountability seem too dispersed.

documenta fifteen art and curation

Some of the work without the context feels ‘simple’ to criticise: in some cases there were slogans translated from various languages which might be read as naïve (e.g. texts made during workshops as ‘positive encouragement’ to artists or as educational slogans). Critics from FAZ called this ‘Waldorfkindergarten’.[24] And whereas there were very different levels of artistic complexity, additionally complicated by presentations of works that were made in various workshops (also with children or in specific artistic work with institutionalised neurodiverse kids), that kind of assertion demonstrates a basic misunderstanding of the curatorial intent and artists’ everyday reality. As ruangrupa stated: ‘Most collectives in the lumbung inter-lokal come from the contexts where the state had failed to support the development of infrastructure and a support system for art and culture.’[25] Such situations were demonstrated in stories from Gaza: the Palestinian painter Mohammed Al Hawarji presented works in an unusual format due to them being cut into pieces in order to be transported out of Gaza (Fig.1); other artists received smuggled paint to work with or as payment. Despite their efforts and hopes for making ‘art for the art’s sake’ their non-political paintings have nonetheless become political.[26] As if to highlight that point, the space where Palestinian art works were exhibited had been vandalised shortly before the exhibition started.

Fig. 1: Image of Mohammed Al Hawarji, Animals (2012), oil painting. Image by AM.

Among the criticised slogans were some that seemed very effective to me. Those banners expressed a general indignation against racism (‘White silence is violence’) and presented decolonial messaging about positionality of artists from the Global South. Other poignant mottos were: ‘My biography seems more interesting than my work’, ‘Dis-integration’, or ‘We want to challenge the narrative… that makes us always appear as a group’ (all from *foundationClass collective). These works as well as art education in general were handled with the utmost respect, as an act of vindication to an art status and as an important gesture of art activism and community service, rather than as an afterthought to entertain some of the audience.

The use of various cheap and accessible materials, like paper cardboard used by the Taring Padi collective for their banners and silhouettes, evoked a DIY aesthetic. But the scarcity of materials for many artists is a reality, such as with the Haitian-Atis Resistans (Resistance Artists), who use a lot of recycled materials, found objects, and even human skulls (Fig. 2); this harsh reality can produce very affective works with depth and complexity that a diamond skull might not. As Ben Davis wrote in his review of the exhibition, documenta 15 provides a show that one might otherwise never be able to see.[27] I recognise it as a grand opportunity for the public and a task that the ruangrupa collective had taken on with optimism and resilience, achieving results despite the challenges they faced, mainly thanks to the lumbung practice that provided a genuinely new exciting quality to documenta.

Fig. 2: Photography of Atis Resistans, Ghetto Biennale at St. Kunigundis Church with sculpture by Andre Eugene, and Leah Gordon’s The Caste Portraits photographies (2012) in the background. Image by AM.

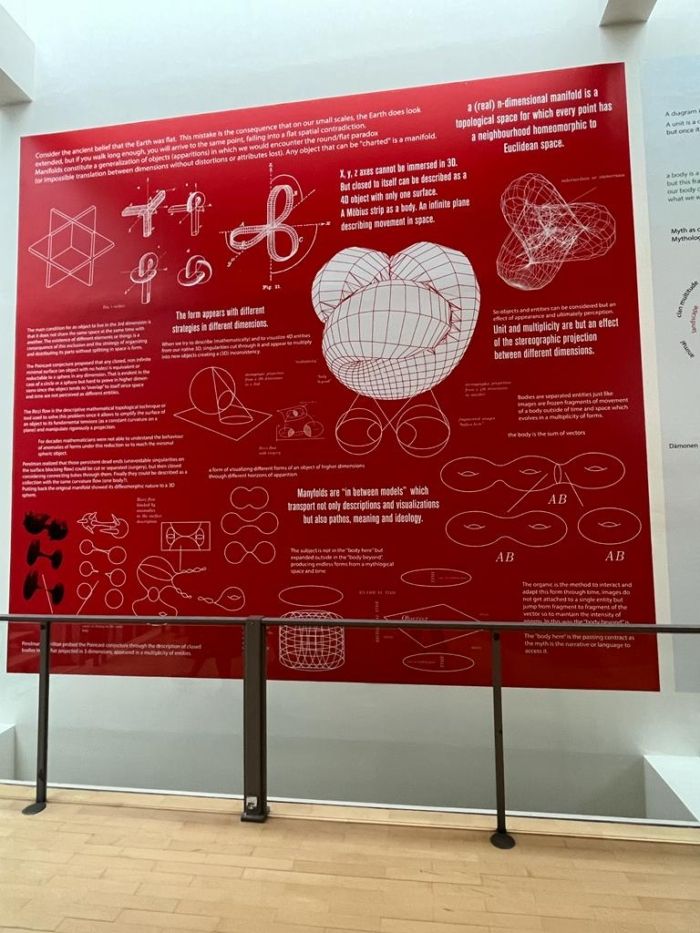

There were many interesting and important contributions feeding lumbung/documenta: the Ghetto Biennial (Atis Resistans) in St. Kunigundis church; works in Fridericianum like the Black Archives; OFF-Biennale Budapest with One Day We Shall Celebrate Again; RomaMoMA at documenta fifteen textile art pieces; or retellings of Palestinian folktales in mixed media such as drawings, video, or objects of cult-like meaning (talismans) focusing on endangered water sites in Palestine by Jumana Emil Abboud. Documenta Halle was set up as a ‘fun space’ with a skate pipe, a show of Wakaliga Uganda’s enjoyable camp film production Football Kommando, and Britto Arts Trust with woven architectural structures outside and a huge mural with Bengali film posters ‘infused’ with anticolonial ironic messaging. Foundation Festival Sur le Niger provided many beautiful objects and installations, connecting art with the artisan woodworking of Mali and the Maaya philosophy beside the traditional rituals enacted on site at Hübner areal. The works from FAFSWAG (Fig. 3), an Arotean group working on the influence of colonisation in the Pacific on the non-binary gender role in Samoan culture, should also be mentioned. Facing the immense abundance of works, I would like to end with Erick Beltrán’s multifaceted work Manifold (Fig. 4), maybe the most ‘contemporary art biennial – like’, with its abstract technological visualisation, an interesting use of historiography and thinking about power versus multiplicity.

Fig. 3: Photography of Māhia Te Kore, Jaimie Waititi, FAFSWAG, The Eyes of Chaos – Pati the Sun (2019), print. Image by AM.

The controversy started in January with an anonymous blog post decrying anti-Semitism due to the connection of some Palestinian artists to the BDS (Boycott, Divestment, and Sanctions) movement.[28] But the big scandal was first connected to the mural People’s Justice by Taring Padi, with anti-Semitic imagery reminiscent of Nazi propaganda from the 1930s, unveiled on the opening night (denounced by FAZ title as ‘Ein Schlag ins Gesicht’ – ‘A hit in the face’ of the German audience). Then, the screening of Japanese archival documentary films (Tokyo Reels) from the early 1980s on the Palestinian struggle with Israel and in Lebanon (Subversive Film) and works of the Archives des Luttes des Femmes en Algérie became problematic. The controversial mural was removed almost immediately, but putting it up without taking into consideration the context of German Jewish history and the sense of guilt that may be present in the country did not prove to be a thoughtful curatorial strategy. However, setting ‘the pain caused by the sequence of events in relation to Taring Padi’s work People’s Justice’[29] aside, one thing is to exhibit the Japanese archives (that in the year of the 50thanniversary of the Munich Olympics attack might be perceived as slightly tone-deaf), and yet another is a ‘scientific’ opinion sourced by the documenta foundation board to recommend a removal of the Tokyo Reels entirely. In the 100 days of documenta 15, the removal and reinstating of some work took place and several non-white artists have been harassed.[30]

It seems that the localisation and translation of lumbung art to Kassel, which ruangrupa highlights as their curatorial goals, has not been entirely successful. One can see that the dispersed, rhizomatic, and non-hierarchical curatorial style, based on the idea of making art differently and resisting its domestication, made this an antagonistic form of curation. As one can see from the documenta 15 curatorial and artistic groups’ letters (published in e-flux) this happened against their own intentions focused on solidarity and community. The director of documenta 15 might have done more to shield the ‘subversive curators’, and also could have negotiated the situation with the German public much better.

The curatorial approach at the Berlin Biennale

The 12th Berlin Biennale was characterised by a strong and clear connection between the exhibition and the place: Berlin and Central Europe. Equally clear is its commitment to enable young artists from the Global South and East to become part of the global art scene/market. The show does not feel especially elitist, despite a possible accusation of ‘the curatorial performance of democracy’.[31] It was inclusive,[32] but not as activist as documenta fifteen.

This year’s Biennale was focused truly on its message, and employed various ways to engage the public more thoughtfully than playfully. However, the programme of lectures, workshops, discussions, and even the action to build a glossary/dictionary added an academic gist to it. One did not feel, by comparison with documenta, like being on a campus of an art school, where creative chaos is a method, catching a glimpse of artists themselves still organising something, rehearsing, making, having fun, etc. The BB12 artists were present through their work, and their messaging was tightly and intentionally woven together into a closed-off whole – the Biennale’s narrative, and the art did not spill out of the containment of the exhibition.

Fig. 4: Photography of an element of work Manifold (2022) by Erick Béltran. Image by AM.

There were beautiful works presented. Almost every work I saw offered something very focused and often contemplative. The works were not easy to ‘digest’, required various forms of engagement, and seemed not to be looking for a shock factor visually, functionally, or in terms of narrative. Attia very thoughtfully used the city, its Central-Europeanness as well as its multicultural character, and made sure the venues were recognised in their own meanings and histories, something that lumbung/documenta 15 somewhat lacked in its approach to see no hierarchy among the venues and choosing those organically, depending on the function and practical needs of each of the involved art collectives.

One of the works connected to Germany and its Nazi past was by Zuzanna Hertzberg, documenting the resistance of Jewish women in ghettos during the Second World War. Others revealed the connection between the city history and its less known layers of embeddedness in Western colonisation, as well as Eastern communist cultural colonisation of Africa; these works came in the form of maps focused on creolising German and decolonial and anti-racist movements in and around Berlin by Moses März, a Berliner artist working to ‘trace movements of Black radical tradition’ alternative to the European liberal paradigm.[33] These works were placed next to an archive of avant-garde journals and art works to create a discussion about the undisclosed African roots of the European avant-garde.

Fig. 5: Photography of a video still from 1941, short film, by Asim Abdulaziz (2021). Image by AM.

Further, works by Noel W. Anderson were powerful and very much on the point of the oppressive (digital) surveillance state that disproportionately attacks Black Americans. His work, a combination of hand and machine work: weaving of cotton tapestry with distorted digital pictures of historical photographs: one of black men being rounded up, undressed and in cuffs (Line up); and another of a search and arrest of another man (Downward dog), among others. The digital distortion reveals the surrealism of this violence and the mechanistic elements of it that are continued further with digital surveillance and digital judiciary (things that were later discussed with Anderson in the Digital Divide conference).

Fig. 6: Photography of Monica de Miranda, Path to the Stars (2022), video still. Image by AM.

Two video works worth mentioning were Asim Abdulaziz’ absurd restaging, featuring Yemeni men, of a Western practice of knitting as a way of dealing with war trauma (Fig. 5), and Monica de Miranda’s interweaving of history and fiction in an Afrofuturistic feminist story developing at the Kwanza River (Fig. 6). Finally, the most strikingly poetic, beautiful, sensitive, and empathetic to its characters, with an effective use of the film and installation formats was the four-channel video installation The Specter of Ancestors Becoming by Tuan Andrew Nguyen, exhibited at the Hamburger Bahnhof. The work drew in with a slow paced narrative of the multifaceted story encompassing several characters belonging to three families in various moments in their life, either in Vietnam or Senegal, during or after the French forces were leaving. The stylised moments ‘captured’ by the cameras seemed particularly real and full of emotion, with a tangible affect for the viewers to feel. There was no turning away from this depiction of the colonial and racial trauma those international families endured due French colonial rule.

Final remarks

The difference in curating or curatorial style between the two shows could be well exemplified by the way the Subversive Film program about Palestinian struggle in the 1980s has been staged at documenta (later removed by the documenta board) versus the work presented in Berlin Biennale on Palestinian immigrants. documenta 15, as ruangrupa states in the catalogue, focused on functionality of spaces and not thematic or specific connections between different works, curatorial, and artistic collaborations and collectives. The films were displayed in a place that was convenient and not directly connected to works exhibited in other rooms. The description of the Subversive Film program was hanging behind the screen in a small cinema built there, and only visible when someone was crossing to another space. This might have added to misunderstanding about showing this project and its meaning in relation to the entirety of the exhibition, though the anti-Palestinian sentiment was probably why the work was removed. The attitude of ruangrupa was one of dispersion of works, freedom provided to every joining curatorial or artistic collective, and making the works function best in the provided space – not to bend them together to an overarching curatorial narrative and not to ‘tame’ them.

The Berlin Biennale’s use of KDW space, instead, and the presentation of the work about Palestinian immigrants in France in 1970s, Exile is hard work, had clear description. Also, as art work in the entrance, it set the tone and made connection with other works on the same floor, that is, photographs of Romas in France (addressing the idea of such ‘anthropological’ work as problematic) and the above-mentioned work on Jewish female freedom fighters of the Warsaw ghetto uprising. The narrative of the curator seemed to be narrower, leaving possibly less room for a variety of interpretations but instead it clearly pointed to commonalities between struggling targeted peoples and to solidarity.

The Berlin Biennale curators have treated the Global South artists as artists from any other region in the sense of their responsibilities in building the curatorial story. It seems that here the road for empowering artists from less privileged contexts was to normalise their presence in long established institutionalised practice with a clear hierarchy of power, tasks, and responsibilities. This inclusion might be a way to promote artists from the Global South on the global art market, as behind the scenes, exclusive sales and usual art gallerists and other buyers’ meetings were happening throughout the biennale’s duration. Meanwhile, documenta fifteen intentionally abandoned treating this exhibition (with almost exclusively non-Western artists) like any other biennale. They dispersed hierarchy of tasks and power, focused on collectives and groups, not singular names, favoured open sale of rather smaller art objects over any behind the scenes sales, and offered a network of artist/teachers/curators continuously co-creating the entirety of the biennale throughout its development, with lots of ‘unsellable’/not monetisable performances and community workshops, complemented with open discussions about funding and about the politicisation of Global South artists. The questions that certainly arise is which curatorial approach – the subdued institutionalised, maybe complacent (to the art market paradigms), inclusive one of Berlin Biennale, or the rhizomatic, critical (of commodification of art), antagonistic or politicised, and inclusive one of documenta – is better for its artists and their works or for art in times of biennialisation?

ruangrupa set their task quite precisely and presented it in various formats, including the explanation of their method of work – lumbung. They provided what they said they would. Art of the Working Class called the exhibition a ‘populist art’, and populist art we have seen in documenta fifteen. We received what the curators promised, and whether the usual audience and more conservative German public expected it or not, whether the director knew what might happen or not, whether all participants were ready for possible issues with that format is not an issue, as there were revolutionary art exhibitions before. But it is obvious that a discussion was lacking, and it was not the curatorial group but the main organizers’ role to assess the context better and oversee the process more. Where there is freedom, democracy, collectivity, dispersed authorship, and dispersed responsibility, misunderstandings might happen and problems might occur. What seems to be at the heart of the struggle in seeing the removal of works as enacting of censorship or as looking for accountability is the question whether the obviously inclusive decolonial empathetic work taken up by ruangrupa and the huge numbers of invited artists and collectives should be undermined or even rejected as a whole because of that. The usually conservative Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung asked questions that are far from the lumbung practice, that are connected to state and local funding, to the documenta 15 director’s work, and to the relationship between this exhibition and the local context, as well as the German legal and social rules and anti-Semitism.

The ongoing development of this controversy provoked Hito Steyerl’s decision to remove her work (due to ‘lack of discussion’), thus leaving a gap in a collective work that was conceived with her art piece. The Anne Frank Institute’s Meron Mendel resigned from advising documenta. Finally, documenta’s director Sabine Schormann resigned.

Hopefully, the value that documenta 15 brought prevails as a very engaging contemporary art initiative, much more connected to the life of less privileged people fighting everyday battles with sexism, racism, ableism, colonialism, and hyper-capitalism than any other exhibition of the same kind.

Despite my enjoyment and ease in experiencing the Berlin Biennale 12 and my understanding of political engagement, this show has not been radical or surprising in the way documenta 15 has. The Berlin Biennale very clearly recognises its Berlin and Central European situatedness, the history of racism, anti-Semitism stances included. But at the same time, it permits a seasoned art audience to feel relaxed and slip easily into a canonical biennale visit format. Conversely, documenta 15 does not permit that: it takes no prisoners but brings wonder and creative chaos back into play. Such a documenta as a cultural and not ‘just artistic’ event is needed.

Finally, the documenta 15 with its dispersed collective curating and shaking of the status quo revealed pertinent questions in times when biennales are seceded or outsourced even to an AI curator (e.g. Bucharest Biennale). The questions of curation formats lead to questions of curators’ responsibility and accountability – that is, who are curators responsible to, and what for? Should their commitment be to art, to community (if so, which community?), to political ideals, to audience, or to market? In short: documenta 15 makes us ask what should the task of curation be now.

Author

Agata Mergler is a PhD candidate in the Humanities Department at York University, Toronto.

References

12th Berlin Biennale for Contemporary Art ‘Still Present!’, exhibition catalogue, Germany 2022

Attia, K. ‘Introduction’ in 12th Berlin Biennale for Contemporary Art ‘Still Present!’, exhibition catalogue, Germany 2022: 22-41.

Davis, B. ‘Documenta 15’s Focus on Populist Art Opens the Door to Art Worlds You Don’t Otherwise See – and May Not Always Want To’, artnet, 2022: https://news.artnet.com/art-world/documenta-15-review-2140149.

Gardner, A. and Green, C. Biennials, triennials, and Documenta – the exhibitions that created contemporary. John Wile & Sons Ltd, 2016.

Kent, E. ‘The History of Conscious Collectivity Behind Ruangrupa’, Art Review Asia, 6 July 2022: https://artreview.com/the-history-of-conscious-collectivity-behind-ruangrupa/.

Roth, C. ‘Prologue to Berlin Biennale’ in 12th Berlin Biennale for Contemporary Art ‘Still Present!’, exhibition catalogue, Germany 2022: 10-11.

ruangrupa. documenta fifteen Handbook. Hatje Cantz, 2022.

ruangrupa. ‘Censorship Must Be Refused – letter from lumbung community’, e-flux, 27 July 2022: https://www.e-flux.com/notes/481665/censorship-must-be-refused-letter-from-lumbung-community.

ruangrupa. ‘We are angry we are sad we are tired we are united – letter from Lumbung community’, e-flux, 10 September 2022: https://www.e-flux.com/announcements/489576/we-are-angry-we-are-sad-we-are-tired-we-are-united-letter-from-lumbung-community/.

Salemy, M. ‘Antisemitism is the Least of Documenta 15 Problems’: Art of the working class, 24 June 2022:

https://artsoftheworkingclass.org/text/antisemitism-is-the-least-of-documenta-fifteens-problems .

Trinks, S. ‘Die Welt als Wille und Waldorfkindergarten’, FAZ, 17 June 2022.

[1] Roth 2022, p. 10.

[2] ruangrupa, documenta fifteen Handbook, p. 30.

[3] Attia 2022, p. 22.

[4] Ibid., p. 28.

[5] ruangrupa, documenta fifteen Handbook, p. 12.

[6] ruangrupa, Sep 10, 2022.

[7] https://universes.art/en/documenta/history

[8] https://www.dw.com/de/documenta-2021-werner-haftmann-deutsches-historisches-museum/a 57935587

[9] ruangrupa, documenta fifteen Handbook, p. 12.

[10] https://ruangrupa.id/en/about/

[11] Kent 2022.

[12] Davis 2022, par. 12

[13] Gardner & Green 2016, p. 257.

[14] https://www.berlinbiennale.de/en/1362/about-us.

[15] There were non-German curators, like Adam Szymczyk (documenta 14) or Documenta 11 curator Okwui Enwezor.

[16] ruangrupa, documenta fifteen Handbook, p. 21.

[17] Ibid., p. 24.

[18] Ibid., pp. 30-31.

[19] Ibid., p. 12.

[20] Ibid., p. 9.

[21] Ibid., p. 12.

[22] Ibid., p. 19.

[23] Salemy 2022, pars. 2 and 6.

[24] see: Trinks, ‘Die Welt als Wille und Waldorfkindergarten’, FAZ, July 2022.

[25] Ibid., p. 24.

[26] As provided in the exhibition text ‘The Political Non-Political Art’.

[27] Davis 2022.

[28] The German parliament declared the BDS movement as anti-Semitic.

[29] ruangrupa, 27 July 2022, par. 3.

[30] ruangrupa, ibid..

[31] Gardner & Green 2016, p. 257.

[32] Once bought, the inexpensive ticket was valid until the last day of the exhibition.

[33] Still Present! 12 Berlin Biennale for Contemporary Art, p. 134.