The biennale as a device: 4th Athens Biennale

It is a cliché to say that times of crisis are good for art. For better or worse, this cliché seems to hold some truth for Greece during the past few years. It might be too early to evaluate the quality of art produced at this time. However, beyond any doubt, in the visual and performing arts there is a strong urge towards production, experimentation, collectivity, and self-organisation with limited visible involvement of art institutions and the market. There is also an increase in critical writing circulating freely online. There is even an emerging Greek cinema (sometimes called the Greek ‘Weird Wave’) present at major international festivals after decades of absence. Similar to the visual and performing arts, cinema also relies heavily on the mutual free exchange of labor and skills among professionals.[1]

If up until the early 2000s the aforementioned local art scenes appeared to be somewhat self-absorbed, trendy, and detached from society that is not the case anymore, at least for a younger generation. The energy and spirit of collectivity and self-organisation have grown parallel to similar tendencies in the social sphere, where after the crisis in 2008 civil initiatives often fill the space of the disintegrated state. Very importantly, several social, cultural, and artistic initiatives share a common ground in the experiences of the 2008 country-wide civil uprising and riots following the shooting of the 16-year-old Alexandros Gregoropoulos, the 2011 occupation of Syntagma square, and the ongoing smaller acts of protest and civil disobedience continuing today. There are important positive aspects and consequences to these experiences, such as the feeling of mobilised collective energy and – particularly after the Syntagma square occupation – the imagining and experience of a political life without the existing, corrupt political parties. However, the downsides are difficult to ignore, most notably the absence of any impact in actual governmental decision-making of the in situ physical, as well as the world-wide mediatised, presence of the hundreds of thousands of ‘indignados’ on squares, streets, and parks. Even more, the public has likely grown tired and immune to the media spectacle of protests and riots.

This existing situation was embraced by the 4th Athens Biennale (AB4) in 2013. Curatorial authorship was divided among a collective of more than 40 members, who in turn invited others not only to show art but also to further curate sections of the program.[2] Resources were limited and contributions mostly voluntary. The organisers see the biennale less as a white cube show and more as an event – particularly the 4th edition in 2013, as a device

that could host actions, collectives, works and so on. It would act as an outer shell: a new convention between the public and creative forces.[3]

AB4 was titled AGORA and used the old Athens Stock Exchange building as its main site, which was abandoned in 2007 when the exchange moved to new premises. Two floors of the old exchange building were used as traditional exhibition galleries, while the large, central atrium-like hall was left almost entirely empty for events. An old machine room upstairs was used as a workshop area. The gallery exhibition was also placed at the nearby art center CAMP.

In the context of contemporary Greece, with five years of deepening crisis, measures, and protests having profoundly transformed daily life, AB4 was meant as a device for the staging of a multitude of positions and responses to the question ‘Now what?’. With this agenda in mind AGORA operated as a platform with multiple physical and virtual sites and tools. I would like to reflect on the relations between the physical and online sites of the biennale as a device. Subsequently I will contemplate how this device staged and mediated the local cultural scene – even though that cultural scene was also appropriated, and probably even exhausted, by the biennale format.

The multiple sites of AGORA

Collective curating in art is not as unusual as people tend to think. The fact is often ignored that even when only one person is commissioned as chief curator – though very often there are two or three for biennales – he/she is supported and surrounded by collaborators and assistants with varying degrees of freedom. However, with few known exceptions (such as the 4th Gwangju Biennale in 2002), it is unusual to have a collective of as many as 45 members horizontally organised, with a lack of knowledge surrounding each others’ input. The curatorial collective was divided into three teams after the popular game ‘rock’ (theory and curation), ‘paper’ (communication and curation), ‘scissors’ (production and curation).

The communication team, comprised of art professionals and others such as journalists and web designers, was the most interesting one. It ran the press office, the web desk (organising and updating the website, posting events to the calendar), and also curated parts of the program, most notably the Open Call and Circle. The Open Call was an open invitation placed on the AGORA website and addressed to ‘everyone who seeks to develop operational approaches and attitudes in today’s critical time’.[4] In total, 382 proposals were posted; they are all still available on the website, with no indication regarding which ones were selected and realised. Circle was a second open call for participation, but this one was specifically meant to fill in a particular program. While the Open Call was without a defined structure and criteria, Circle set a particular theme for every Sunday, such as ‘city’, ‘human rights’, ‘collaboration’, and ‘ecology’. Any relevant organisation or other initiative was welcome to apply with a 15-minute presentation.

In practice the biennale as an ‘agora’ was made possible by and also partly took place online. The AGORA website enabled the public announcement of the Open Call and Cycle in addition to hosting, in a permanent, indiscriminate, and non-hierarchical manner, all proposals that were posted. Moreover, as the program of events was only roughly in shape for the opening in September and each week’s program was practically finalised just in time for the email newsletter posted every Monday, the website was the one and only source of (usually) valid information about the calendar of events. On the AB4 website one could also find a continuous live stream of events at the central hall, some ongoing online projects (Open Call, Circle, Event as Process),[5] and a roughly-edited archive of videos from selected events, interviews with participants, etc. Weeks before the opening another public invitation called for anyone interested to post content on the AGORA Instagram and Facebook pages, both of which were used extensively. The AGORA Facebook page was the site where links to exhibition reviews, images, and various announcements were posted. One could actually follow the dense activity and gain more insight by accessing the Facebook pages of some of the curators who posted impressions from different events.

Altogether, it was hardly possible to evaluate the success of the biennale in implementing its vision after just visiting the gallery spaces or even following a couple of events. It would also be frustrating to try to experience just the physical or the online sites. Due to the multi-centred but also last-minute and somewhat chaotic development of the program, the physical and virtual sites depended upon one another in providing some kind of operational structure to the content of the entire, process-based biennale device/project.

Aesthetics of information, participation, and activity

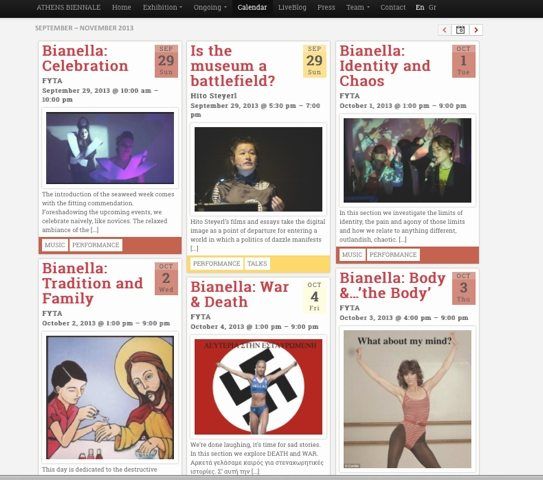

If one could best characterise the form of the information on the AGORA website it would be the database and the alphabetical inventory, both rigidly organised within pre-set categories but also keeping all individual curators, participants, and contributors at an equal level of visibility and importance. This applies to the list of the curatorial team, the block of names of ‘The AB4 artists, projects and other participants’ that was published online when AGORA started and was later filtered into an alphabetical inventory, or to the posterboard calendar where each event was granted a box and placed under categories. A posterboard with similar categories and chronological order of posting, but applying slightly different interface templates (with bigger images, subtitled only by author and project title with more text appearing after clicking), was used for the Open Call. Moreover, an equalising effect was also produced by the ongoing live-streamed video, as a camera was continuously broadcasting from the central hall regardless whether events were taking place or not. With a camera often placed at a high-angle without moving in for close-ups or changing viewpoints, and relying on microphones for sound, the live-stream was sometimes identical to the images and aesthetics of surveillance cameras[6] – potentially creating yet another database with endless hours of video footage.

Events and activities were happening daily within the physical site of the central hall. Unlike most biennales, some curators were regularly present. As is the case in a real ‘marketplace’ (the meaning of ‘agora’ in modern Greek), one had the feeling of ongoing activity picking up and subsiding according to day and time, with the audience shifting hubs between the improvised auditorium and the bar, not unlike in a festival where event dynamics change according to the energy and audience attention. Some people I talked to expressed the impression that the organisers seemed to have invested more into the feeling of ongoing activity with variety and participation rather than to the content. Watching online during and after the events (last visited on 8 February 2014), including the post-biennale trailer and various video fragments which are now part of the publicly-accessible archive of AGORA, great emphasis is indeed given to the feeling of activity, the alteration of happenings, and energy. However, after the biennale ended a stronger curated selection of videos was added, allowing the online audience a better view into the content.

Between entropy and potentiality

In situ and online, AGORA staged and archived multiple individual and collective contributions in many forms of expression – conference, workshop, performance, theatre, lecture, concert, roundtable, online reader, etc. – with somewhat dodgy organisation but a focused aim. In conceiving and realising such an event, AGORA was innovative among biennales.[7] However, within the local Athenian cultural, social, and political landscape, it staged and amplified a commonly-known situation: the existence of multiple networks of collective artistic, social, and political initiatives that practically and emotionally, altruistically or opportunistically, live and online, have been processing and reacting to the crisis for years through their presence and activities. Growing in an organic fashion, they have found, created, or appropriated stages for visibility such as, for instance, the occupied theatre Embros.

Nobody expects an art event to directly influence state politics. The all-inclusive and affirmative two-and-a-half months of AGORA indeed brought together multiple energies and perspectives. However, a question arises about how AB4 addressed the politics of public melancholy and exhaustion. As mentioned earlier, since 2008 there have been several occasions of collective action and activity communicated by mass as well as alternative media and events. What differentiates entropy from potentiality when the energy of a multitude is streamed into a continuous but not self-generated flow of activity and transcribed into online databases?

Browsing through the archived videos months after the end of the show and while myself slipping into entropy, I came across a four-minute interview with artist and writer Hito Steyerl that took place on the stairs of the Athens Stock Exchange on 26 October 2013. Asked about her experience there she replied:

[w]hat was my experience here? Questioning the term ‘experience’ was a crucial moment in [my] talk. What does it mean in an economy that is so much based on spectacle? What is an experience? Can we still have an authentic experience, or is it dissolved somehow in the society of spectacle, commodification, of city marketing and so on and so on? But in the talk I was replacing this with the term ‘education’. Regardless whether you have an experience or not you can still get the education. Sometimes even under the most difficult circumstances which would be able to give you the most cutting-edge education, and I feel that this is what I experienced here.[8]

Eva Fotiadi (University of Amsterdam)

References

Bailey, S. ‘Athens, baby: A conversation with Poka-Yio’. http://rhizome.org/editorial/2013/nov/5/athens-baby-poka-yio-conversation-stephanie-bailey/ (accessed on 27 December 2014).

Papadimitriou, L. ‘Contemporary Greek cinema: Directions, prospects and exchanges’, paper presented at the 23rd MGSA Symposium, Bloomington, Indiana, 16 November 2013.

[1] Papadimitriou 2013.

[3] Bailey 2013.

[4] ‘Now what? By bringing into play the collaborative process in its production, the 4th Athens Biennale answers this question by creating the conditions for the creative contribution of everyone who seeks to develop operational approaches and attitudes in today’s critical time. Check out the call & guidelines and use the submission form to contribute with your entries!’ Open Call text, http://athensbiennale.org/en/agora_en/open_call_en/#open_call_blog (accessed on 13 February 2014).

[5] I was the co-editor of the online compilation of articles titled Event as Process: Cities in an Ongoing State of Emergency and the Artists’ Stance. It was created following a carte blanche invitation for a contribution to the theory program.

[6] This description refers to the times I watched the live stream, which is impossible to write about in its entirety.

[7] The scope of events on a daily basis reminds one of Documenta X, curated by Catherine David. An important difference is that David used this format to include contributions from around the world that would not necessarily be accommodated by the Western art framework of the white cube, whereas in AB4 the local Greek and non-Greek scene played central roles.

[8] Interview with artists Fernardo Garcia-Dory, Tania Bruguera, Geof Oppenheimer, and Hito Steyerl. http://athensbiennale.org/category/liveblog/ (accessed on 13 December 2014)

Comments are closed.